I received two nice holiday gifties: My recent essay on race, genetics, and the Nicholas Wade affair heads up Nature’s top 10 list of Books & Arts pieces for 2014. <blows […]

Here Lies Truth

I received two nice holiday gifties: My recent essay on race, genetics, and the Nicholas Wade affair heads up Nature’s top 10 list of Books & Arts pieces for 2014. <blows […]

It’s pledge week again on National Public Radio. Imagine if Bill Gates had called in and told them, “What’s your fundraising goal for this drive? I’ll meet your target right now if you’ll call off the drive”– and NPR said, “Thanks but no thanks—we’ll see what we can get on the phones.”

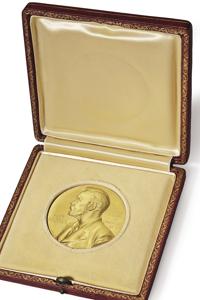

It turns out that’s what happened with Watson’s Nobel medal. Christie’s whispered word about the auction in several countries before the sale. Alisher Usmanov, the richest man in Russia, contacted Watson before the auction and made an offer for a financial contribution to the Lab, on the condition that Watson call off the auction, according to the latest report by Anemona Hartocollis in the New York Times (she’s had the Watson auction beat). But Watson turned down Usmanov’s offer. Hartocollis reports that Watson wanted to see how much he could get for the medal.

So Usmanov let Watson hold the auction and then bid on the medal, determined to win—but to not take home his thank-you coffee mug. As one astute Genotopia commenter observed, things have reached a strange state when a Russian oligarch takes the moral high ground.

This latest twist is vintage Watson. I can well imagine him waving away the rotund Russian and his “boring” (my imagining of Watson’s word) offer of a straight gift. I think the thrill of the gamble caught him. Crick (‘s family) got $2.1M for his. Watson was confident he could beat that. But by how much? At the auction, he watched the bidding intently, grinned broadly when it crossed $4M, and celebrated afterward.

In remarks at Christie’s before the auction, he told the audience to always “go for gold.” Silver was never enough, he said. It turns out that he had something specific in mind: he wanted not the “silver” of Usmanov’s initial offer, but the maximum gold he could get for his gold. The gamble, the risk, the competition, the publicity. The chance to take the stage once again, to rile people up, confuse them, yank the public’s chain. It became about him, not the gift.

Watson enjoys playing the scoundrel and he chose, with classic perversity, to punch a few holes in this clichéd last refuge. The reasons to undertake philanthropy are to be–or at least appear–moral, generous, selfless, humane. As the dust settles on this latest bizarre event in Watson’s long career, he ends up seeming competitive, avaricious, and childish. Of all the reasons he gave for wanting to sell the medal, the most oddly touching was the wish to rehabilitate his image. Alas, he has only reinforced it.

Just when we thought that the Jim Watson Nobel medal story couldn’t get any weirder, the anonymous bidder who won the medal last week is returning it.

The medal-winner revealed himself to be Alisher Usmanov, the richest man in Russia. He is paying the total $4.68 million but insists Watson keep the medal. His gesture appears to be one of generosity—but is it really?

The medal-winner revealed himself to be Alisher Usmanov, the richest man in Russia. He is paying the total $4.68 million but insists Watson keep the medal. His gesture appears to be one of generosity—but is it really?

“In my opinion,” Usmanov said, “a situation in which an outstanding scientist has to sell a medal recognising his achievements is unacceptable.” He added, “James Watson is one of the greatest biologists in the history of mankind and his award for the discovery of DNA structure must belong to him.” In short, Usmanov used the auction as a means of making a more than $4M donation to scientific research.

As I wrote the other day, it’s not true that Watson had to sell his medal—he’s hardly eating cat food. Usmanov’s stipulation that the money go to research tacitly acknowledges this fact. Triangulating—or rather, heptangulating—on Watson’s numerous statements about what he would to do with the money, he probably intended to keep a chunk of it, but give most of it away. Although he mused about giving to each of the schools that were primary to his education, experience suggests that most will go to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (always his favorite charity). We—or anyway I—will be watching for an announcement in the near future about the endowment of a new Cold Spring Harbor fellowship, probably for young scientists.

So much for the Hockney, though.

But there remains the question of whether Usmanov is doing Watson a favor by returning the medal. Usmanov has upstaged Watson, foiling any effort for Watson to rehabilitate his image through major charitable giving. Watson still has the $600k from the sale of the documents, which went to a different bidder, but that is a small fraction of what his total gift could have been.

Is Usmanov’s gesture a well-intentioned blunder or is it philanthropic one-upsmanship? By returning the medal, Usmanov is simultaneously contributing to scientific research and throttling Watson’s effort to do the same.

If, on the other hand, Watson’s only intention was to raise money for the Lab, then he gets to have his medal and sell it too. I think we can dispense with the prospect of his turning around and selling it again—that seems too cheeky even for Watson. But who knows? Every time he goes out for a long one, he seems to do a double reverse.

The one safe conclusion is that deterministic explanations rarely fit Watson’s actions. A single motivation almost never fully accounts for what he says. Darwin knows, Watson says much that deserves criticism. But anyone who takes his remarks at face value misunderestimates him, is more interested in self-congratulatory castigation than genuine understanding, or some combination of the two.

Colleagues, writers, readers, hear me for my cause…I come not to bury Watson, but to historicize him.

James Watson has not been in the news much in recent years. In fact, he has been lying low since 2007, when he said he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa,” because “all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours whereas all the testing says not really,” and was removed from the official leadership of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Prior to that, he had for decades been a staple of science gossip. No one has ever suggested that he embezzled money, cheated on his wife, or beat anyone up; his scandals have all been verbal. If there were a People magazine for science, Watson would have been its Kanye West.

But last week, he was once again making headlines and enemies—this time with his auction of his Nobel Prize medal and the original drafts and typescripts of his Nobel speeches. The medal sold for $4.1 million, with another $600,000 for the documents. The event was a good deal more interesting than you might think.

Facebook and Twitter have been venting all week, the public’s ire only fueled by Watson’s public statements. In an interview with the Financial Times, Watson said several things that made right-thinking people go ballistic. (A link to this and a selective list of other major articles is at the bottom of this post.) He suggested he was financially hard up, as a result of being made a pariah since 2007. “Because I was an ‘unperson,’” he said, “I was fired from the boards of companies, so I have no income, apart from my academic income.” And yet, he wanted to buy art: “I really would love to own a [painting by David] Hockney,” he said. He iced it by insisting that he was “not a racist in a conventional way,” which sounds a lot like he was confessing to be an unconventional racist. Watson’s admirers buried their faces in their hands once again.

Watson, however, has not been the only one to thoughtlessly voice ill-considered views. In response, serious scholars expressed such nuanced positions as “Watson is a professional dickhead,” and “I no longer want to hear what [he has] to say.” “He’s a misogynist,” wrote one person on my feed. “…And don’t forget a homophobe,” chimed in another; “Yes of course,” replied the first, “I took that for granted.” Back-slapping all around, with much self-congratulation and smugness. That’s not analysis; it’s virtue-signaling.

The mainstream media hasn’t been much better. In Slate, Laura Helmuth achieved the trifecta of yellow journalism: inaccuracy, hyperbole, and ad hominem attack. Her article, “Jim Watson Throws a Fit,” asserted that Watson was “insuring [sic] that the introduction to every obituary would remember him as a jerk.” In her professional analysis, “he has always been a horrible person.” Always? I would love to borrow Helmuth’s time machine: I have a lot of gaps I’d like to fill in. Watson, Helmuth coolly noted, “knows fuck all about history, human evolution, anthropology, sociology, psychology, or any rigorous study of intelligence or race.” Serious academics whooped and cheered.

Helmuth, however, knows fuck-all about Watson; her piece is riddled with inaccuracies, rumor, and misinformation. Nevertheless, she exhorted Slate readers not to bid on the Watson medal. I admit I did follow her advice—and for the foreseeable future I’m also boycotting Lamborghini, Rolex, and Lear Jet.

Most surprising to me was the generally serious Washington Post. Like many people, I think of WaPo as a sort of political New York Times: tilting slightly leftward but mainly committed to high standards of journalism. But they headlined their article, “The father of DNA is selling his Nobel prize because everyone thinks he’s racist.” That sounds more like the National Enquirer than the Washington Post. Elsewhere, several articles referred to him as the “disgraced scientist” or “disgraced Nobel laureate.”

Watson-haters may jump down my throat for what follows, on the premise that I am defending Watson. Watson-lovers (dwindling in number, but still more numerous than you might think) may believe I fail to defend him enough. What I want to do is cut through the hyperbole, the ignorance, and the emotion, and attempt to do good history on a challenging, unpopular, and fascinating biographical subject. Watson has much to reveal about the history, the comedy, and the tragedy of 20th century biomedicine.

*

I have known and watched Watson for nearly 15 years. A year ago, I published in Science magazine a review of his Annotated, Illustrated Double Helix. I used the review to argue that in his treatment of Rosalind Franklin, Watson was conveying Maurice Wilkins’s view of her. In 1952-53, Watson scarcely knew Franklin, and later, Crick became good friends with her. Wilkins, however, hated her. The feeling was mutual and stemmed, at least in part, from lab director JT Randall’s bungled hiring of Franklin. Wilkins may well have been sexist, but probably not unusually so for his day. Ditto Watson and Crick. But in The Double Helix, Watson wanted to curry favor with Wilkins—his prime competitor and fellow laureate. The Double Helix is part history, part farce. It is naive to read it prima facie.

I had thought the review critical, but to my surprise and his credit, Watson loved it. He wrote me a personal note, saying that I was the first Double Helix reviewer who had gotten him, Wilkins, and Franklin right. (Against myself, I must note that Horace Judson was the first person to note that Watson and Crick’s principal competition in the Double Helix was not with Linus Pauling, but with Franklin and Wilkins.)

Based on the Science review, Watson requested me to write an essay for the auction catalogue. In addition to the medal, he was selling a draft of his Nobel speech and a complete set of drafts of his “Banquet” speech. A medal’s a medal; these documents were what piqued my interest. Since my current book project is on the history of DNA, it was literally a golden opportunity. Further, I would have unlimited personal access to Watson (he turns down most interview requests, especially from historians). I would of course be invited to attend the auction. In full disclosure, Christie’s naturally paid me an honorarium for my writing; I charged them as I would charge any private, for-profit company. Watson himself has paid me nothing.

When Christie’s broke the story of the auction, the press and the blogosphere pounced. Many people’s immediate reaction to the news was disgust, a sense that he was disrespecting the award. Two principal questions were on everyone’s mind. In formal interviews, public comments, and private statements, Watson obliged with a bewildering array of answers.

Why was he doing it?

What is he doing with the money?

Several observations immediately pop out of this. First, he plans to give away at least most of the money. Almost everything he has said involves charity, although in some cases (e.g., the Hockney—see below), this was not obvious. Most of these non-obvious gifts would go to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory—always Watson’s favorite charity.

Second, his eyes are bigger than his wallet. Reasonable estimates for an endowed lectureship are $250,000 and about $750,000 per student for graduate fellowships (http://www.gs.emory.edu/giving/priorities/naming_policy.html). A Hockney oil could cost more than Watson’s medal: they routinely fetch $7M–$8M (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2045824/Modest-British-artist-David-Hockney-74-worth-staggering-80-million.html).

On the Hockney, Watson said at the auction that in fact he “already had a couple of Hockneys.” He has a decades-long relationship with the artist, dating back, he said, to when Hockney offered to draw him, did so, handed him a print—unsigned—and then put the signed original up for sale. Watson laughed that he had to buy back the drawing he had been offered. He said he had no Hockney oils, however. But nor did he have any space in his house for a Hockney: his intention was to hang it in one of the Laboratory’s buildings. For many years, Watson has been decorating the Lab grounds with artwork. Reasonable minds may disagree about the need for a scientific laboratory to boast millions’ worth of art, but Watson wants Cold Spring Harbor to be a place of beauty and even luxury.

Third, it’s foolish to take his outlandish statements at face value. Most articles about the auction seized upon one of his remarks and presented it as “the truth” about what Watson thinks. That’s even worse than reading The Double Helix as straight memoir. Watson loves pissing people off—he may well have deliberately misled the media. Perverse, given the rationale of burnishing his image, but not for that reason ridiculous. He simply is not consistent. That inconsistency is something to explain, not brush aside.

Watson has always cultivated a loose-cannon image: having no filters has been part of his shtick. He has been observed deliberately untying his shoes before entering board meetings. But in his prime, he could usually filter himself when necessary. Nowadays, he keeps his shoes tied. Although he is clearly compos mentis, his ability to regulate his filters may have slipped. He’s always been cagier than he’s been given credit for, but his loose-cannon image is becoming less of an image and more of a trait. The quality he has nurtured, one might say, is becoming part of his nature.

*

Which raises the question: Is Watson merely a crank? Clearly, many in the science community believe he hurts the image of science and is best simply ignored. They treat him as an outlier, an aberration: someone whose views do not represent science or what science stands for.

I have a different view.

Granted, Watson is extreme in his candor; even his staunchest allies admit that he over-shares. But for both better and worse, he is emblematic of late twentieth-century American science. His lack of filters, not just over the past few days but over the last few decades, throws a harsh but clear light on science. He was there at the creation of molecular biology. Through his guileless but often brilliant writing, speaking, and administration, he has done as much as anyone to establish DNA as the basis for modern biomedicine and as a symbol of contemporary culture. He has helped reconfigure biology, from a noble pursuit for a kind of truth into an immensely profitable industry. Thanks in part to Watson, some students now go into science for the money. It has been said that in transforming Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory into a plush campus, filled with gleaming high-tech labs, posh conferences, and manicured grounds full of artwork, Watson made Cold Spring Harbor into a place where the young Jim Watson could never have flourished. The same can be said about his role in science as a whole.

The remarks Watson has made about women and minorities are emblematic of the late 20th century. His comments focusing on women’s looks rather than their intelligence are precisely the kinds of comments feminists have fought against since The Feminist Mystique was published, the year after Watson won the Nobel. Although such comments are thankfully much less tolerated than they once were, far too many men still objectify women. Once again, this is not to forgive his remarks; rather, it is to demand thoughtful explanation.

As to race: we are a racist society. From the time the first British and French landed on these shores, whites have condescended to and exploited every non-WASP ethnicity they have encountered: Native Americans, Africans and their descendants, Latinos, Asians, Jews, Irish, Poles, Italians. And many of those groups have then turned around and condescended to and exploited others. In his book of last summer, the New York Times science reporter Nicholas Wade wrote that anti-racism in this country is now “so well-entrenched” that we can afford to ask “politically incorrect” scientific questions about racial differences in intelligence. The current protests over police brutality toward black men in Ferguson, Missouri and Staten Island, New York, and elsewhere say otherwise.

Were Watson merely a rich old white guy who says retrograde things about race and gender, he could—and arguably should—be ignored. What makes Watson different is that he sees everything in terms of genetics–and not much else. In New York this week, he said that if one looked hard enough, one could find a genetic correlation with Baptism or with being a Democrat. One can probably find a “gene for” essentially anything. Genomic analysis is now so fine-grained, so precise, that the definition of “trait” is arbitrary. The problem is not that Watson is wrong about these presumptive correlations, but that it’s meaningless. The project of finding the genetic basis of everything has become too easy, too inexpensive, too powerful. His style of genetic determinism may again be more extreme than most, but his scientism (crudely, the belief that all social problems can be addressed with science) generally is common and becoming commoner.

Watson, then, shows us what happens when a typical man of the twentieth century thinks about genetics too much. James Watson is worth listening to, is worth understanding, because he represents both the glory and the villainy of twentieth-century science. He may not be easy to listen to, but neither was the viral video of Daniel Pantaleo choking Eric Garner easy to watch. If we shut our ears to Watson, we risk failing to understand the pitfalls of the blinkered belief that science alone can solve our social problems. Those who resort to simplistic name-calling do little more than reiterate their own good, right-thinking liberal stance. Doing so may achieve social bonding, but it gains no ground on the problems of racism, sexism, and scientism. Those who think the conversation ends with playground taunts are doing no more to solve our problems than Megyn Kelly or Bill O’Reilly. Calling Watson a dickhead is simply doing Fox News for liberals.

What is the corrective? Rigorous humanistic analysis of the history and social context of science and technology. Science is the dominant cultural and intellectual enterprise of our time. Since the end of the Cold War, biology has been the most dominant of the sciences. To realize its potential it needs not more, better, faster, but slower, more reflective, more humane.

I share the romantic vision of science: the quest for reliable knowledge, the ethos of self-correction and integrity, the effort to turn knowledge to human benefit. And at its best it achieves that. But science has a darker side as well. Scientific advance has cured disease and created it; created jobs and destroyed them; fought racism and fomented it. Watson indeed is not a racist in the conventional sense. But because he sees the world through DNA-tinted glasses, he is unaware of concepts such as scientific racism—the long tradition of using science’s cultural authority to bolster the racial views of those in power. Historians of science and medicine have examined this in detail, documented it with correspondence, meeting minutes, and memoranda. Intelligent critique of science is not simple “political correctness”—it is just as rigorous (and just as subjective) as good science. The more dominant science becomes in our culture, the more we need the humanities to analyze it, historicize it, set it in its wider social context. Science cheerleading is not enough.

The trouble with Watson, then, is not how aberrant he is, but how conventional. He is no more—but no less—than an embodiment of late twentieth-century biomedicine. He exemplifies how a near-exclusive focus on the genetic basis of human behavior and social problems tends to sclerose them into a biologically determinist status quo. How that process occurs seems to me eminently worth observing and thinking about. Watson is an enigmatic character. He has managed his image carefully, if not always shrewdly. It is impossible to know what he “really thinks” on most issues, but I do believe this much: he believes that his main sin has been excessive honesty. He thinks he is simply saying what most people are afraid to say.

Unfortunately, he may be right.

**

Here is a selective list of some of the highest-profile articles about Watson and the Nobel medal auction:

11/27/2014 “James Watson to sell Nobel prize medal he won for double helix discovery” (The Telegraph)

11/28/2014 “James Watson to Sell Nobel Medal” (Financial Times)

12/01/2014 “The father of DNA is selling his Nobel prize because everyone thinks he’s racist” (Washington Post”)

12/1/2014 “James Watson Throws a Fit” (originally titled, “James Watson is Selling Off His Nobel Prize: Please Do Not Bid On It”) (Slate)

12/02/2014: “Disgraced scientist James Watson puts DNA Nobel Prize up for auction, will donate part of the proceeds” (New York Daily News)

12/02/2014 “Jim Watson’s Nobel Prize Could Be Yours…For Just $3.5 Million” (Scientific American)

12/3/2014 “By Selling Prize, a DNA Pioneer Seeks Redemption” (New York Times)

12/04/2014 “Watson’s Nobel Prize Medal for Decoding DNA Fetches $4.1 Million at an Auction” (New York Times)

12/04/2014 “Watson’s Nobel Medal Sells for US$4.1M” (Nature)

12/05/2014 “James Watson’s DNA Nobel Prize sells for $4.8M” (BBC) [incorrect: their figure includes the “buyer’s premium,” i.e., the cut for the house]

My recent review in Nature of Nicholas Wade‘s, Michael Yudell‘s, and Robert Sussman‘s new books criticizes all three. The first comes out of the political right wing and is slyly allied with the racist, Pioneer-Funded scientific camp; the latter two identify with the Left’s argument that race is purely a cultural construct. Wade’s argument is far more dangerous than Yudell’s or Sussman’s, but I didn’t like any of the books. It is just as wrong-headed to argue that science proves that race isn’t genetic as it is to argue that it is.

Interesting, then, that the Orwellian HBD crowd, whose newspeak renders white power as “biodiversity” and anti-racism “new creationism,” is jumping down my throat for criticizing their current darling but ignoring my criticism of their antagonists. Since the piece came out, I’ve fended off attacks on Twitter and on white-supremacist sites (Nature wouldn’t let me call them that; it’s good to get it off my chest) such as Stormfront (I refuse to link to them; you can Google it if you want).

And then this missive from Larry Arnhart, a not-quite Dead White Male political scientist:

Dear Professor Comfort,You might have some interest in my blog post on your Nature review: http://darwinianconservatism.blogspot.com/2014/09/the-confusion-in-scientific-study-of.html

Very little, in fact. The gist of Professor Arnhart’s argument is that he doesn’t understand mine. Actually, I’ll give him that much–his commentary makes it abundantly clear that he can’t follow the thread of my reasoning. But that’s a pretty weak rhetorical position, n’est pas? If the book reviews in Nature are over his head, perhaps he should stick with lighter fare.

Arnhart’s basic stance is typical of the people who like Wade’s book. Darwinism, they say, is inherently a politically conservative ideology. This is laughable. Shall we start with those ardent Darwinians Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels? From them forward, a thick cord of Leftist Darwinian thought courses through the history of evolutionary biology, down through Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould.

A cord of right-wing politics, similar in girth, twines around it. You have your Herbert Spencer , your William Graham Sumner, your Charles Davenport, etc., on up to Jared Taylor. But really, are those the kind of people you want to associate with?

One important difference between Marxist Darwinians and right-wing Darwinians is that the Marxists don’t use Darwin to justify their politics the way the right-wingers do. The HBD types wrap themselves in the flag of Darwinism–and anything one says against them is taken as unpatriotic to Darwin and to science.

You can use science, just as you can use history, to support any ideology you want. But Darwinism has not been kind to right-wingers–it tends to make them look like ignorant bigots.

The HBDers hide their faces behind a cardboard Darwin stapled to a stick. They make that gentle and egalitarian soul stand for hatred, arrogance, and xenophobia. It must be the most cynical appropriation of science I’ve ever seen.

I get some flak for criticizing biomedicine. But science is not–and should not be–a sacred cow. Withstanding criticism and becoming stronger for it is one of the qualities that unites scholarship and science.

My critique of science is about hype, oversell, and corporatization, not evidence. When it’s a matter of evidence vs. politics or superstition, I stand arm-in-arm with science. On evolution. On race. And on climate change.

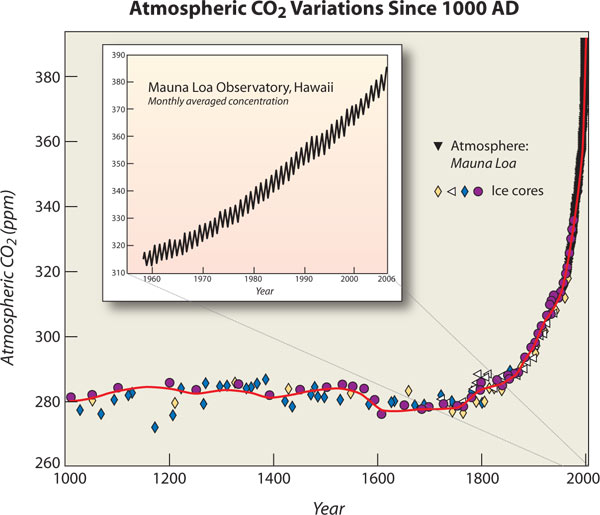

Wish I could have been in New York for the People’s Climate March. But there is just no denying the evidence anymore. I know the climate deniers make their own graphs–it’s a good example of how ideology can be drawn into charts as well as essays. But the consensus is clear, and it’s not just a bunch of liberal Chicken Littles. We’re losing Florida, man. And the reason is clear. The Collapse of Western Civilization, the new genre-bending book from the distinguished historians of science Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, is at the top of my reading pile. Check it out.

I’ve run across this chestnut from NdGT before, but this time it struck me as both untrue and misleading. Of course in a crude sense it’s true. When you get on an airplane, it flies thanks to Bernoulli’s principle whether you believe in or even know of Bernoulli’s principle.

But in a deeper sense it fundamentally misrepresents the nature of science. The good thing about science is not that it’s true–it’s that it’s open to revision. Science’s truths are constantly in flux. As John McPhee said, “science erases what was formerly true.” It’s time to abandon the science cheerleaders’ trope that science is about finding the truth about nature. Every scientific fact ever discovered, every scientific theory ever put forward, is eventually rejected, revised, or limited. The beauty of science isn’t that it’s right–it’s that it can be proven wrong.

The statement is misleading because it is actually more true of religion than science. In his essay “Science and Theology as Art Forms” (Possible Worlds, 1928), JBS Haldane made the point about Christianity, although it holds for certain other religions as well: its gravest problem is its view that it is only true if you believe in it. Hinduism, Buddhism, and many, many others do not hold this view. They hold that their beliefs are true whether you believe in them or not. Karma, for example, just is. It doesn’t matter to a Hindu whether you believe in karma–the wheel will turn on you just the same.

The good thing about good science popularization is that it’s true, period. At a time when science is under fire from fundamentalists, we need to make sure that what we say about rational inquiry into nature is accurate.

My review of Nicholas Wade, Michael Yudell, and Robert Sussman leads off Nature‘s Fall Books number and is featured in the Nature/SciAm Diversity special. And it’s free–no paywall!

This is the piece I was writing when the brick hit my deck, inspiring this earlier post, which is now a finalist for the 3QuarksDaily science blog prize. For a more detailed and absolutely deadpan look at Wade, see Dick Dorkins’s review.

Genotopia’s article “On city life, the history of science, and the genetics of race” has made the top 10 in the 3QuarksDaily science blog contest! Finalists will be judged by the distinguished primatologist and popular author Frans de Waal. Bite your fingernails for me–and stay tuned for further details.

[Edit: I’ve had many positive comments on this post but one negative one keeps coming up, so I want to address it. A few people have felt it makes those who give to ALS feel stupid or duped. Not my intention at all. I’ve had it with ice buckets, not ice-bucket donors. My criticism is of a system, not individual people. I’ve added a line to the disclaimers to address the ALS donors, who obviously are acting with good intentions.]

I’ve had it with ice buckets.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease) is the disease of the moment. Not because it’s the most important medical problem today, but because it’s got a clever bit of marketing that got lucky and went viral. Kudos to the ALS Association’s ad campaign person. The ice-bucket gimmick has nothing to do with ALS—you could ice-bucket rectal cancer just as logically. Maybe more so, in fact, given most people’s physiological response to a couple gallons of ice-water. But hey, for whatever reasons, it has worked brilliantly. But I’m not dumping water on my head and I’m not writing the ALS Association a check. Giving money to biomedical research is like loaning Bill Gates busfare.

There’s a long list of people who could be pissed off at that position, so before I make my case, a few disclaimers:

First, I have great empathy for patients with ALS and their families and loved ones. It’s an awful disease and I hope a cure or at least an effective treatment is found. Soon. I am all for curing ALS. Also, the ALS Association is a fine charity. According to Charity Navigator, they have a high degree of transparency and use only a small percentage of their money for administrative costs. Also, I don’t mean to make those who have already given to ALS feel bad or misled. There’s always a benefit with an act guided by conscience. I’m just going to make the case that the charitable bang/buck is small.

Finally, I feel for scientists. I recognize that funding for the National Institutes of Health—the major federal agency for biomedical research—has been cut this year. But still, I don’t see biomedicine hurting seriously for money. I think that of all the industries that are working with tighter budget constraints, relatively speaking, science is not feeling the most pain, and offsetting its budget cutbacks is not going to have much effect on how soon a great new drug for ALS is found. I love science because it’s cool. But as charity goes, I think it is a pretty low return on investment. Here’s why.

*

I study biomedicine as a social enterprise. I look at it in the context of its history and in the context of contemporary society and culture. The majority of breakthroughs in basic science and almost all translations of basic science into new drugs and other therapies occur in the top university medical schools. I happen to work at one of them; the other biggies include U.C. San Francisco, Harvard Medical School and associated Boston-area hospitals, Baylor, Memorial Sloan-Kettering, Michigan, and a few others.

Science is kind of like a country club, in that it’s hard to get in and those who do have money. In order to enter an elite science building, you probably have to get past a security guard. Inside, there is wood paneling, lots of glass, gleaming chrome, polished floors. It’s like Google, only with worse food. If your building does not look like this—if it’s more than 20 years old—there is probably a fundraising campaign to replace it with something swankier.

It looks corporate because it is corporate. A lab is basically a business. Principal Investigators (PI’s, i.e. faculty lab heads) are entrepreneurs. Their principal role is development; i.e., raising money. The company staff consists of graduate students, postdocs, and technicians, and however many administrators you can afford. It’s a for-profit business, in that all or part of the PI’s salary comes from grants. Often, PI’s also literally run companies on the side; a PI without a little start-up is ever so slightly suspect, as though she’s perhaps not quite ambitious enough for the big leagues. A cut in federal funding means that competition for grants will be stiffer. But the elite schools, where most (not all, I recognize) of the most fundable grant applications come from, have “bridge funding” to help such investigators. The system can absorb some cuts.

The scientific community as a whole is rich, white, smart, and obviously highly educated. Getting one of these PI jobs takes brains, dedication, and in most cases, a good family background. Many scientists have parents who were scientists, and most come from middle- to upper-middle class backgrounds. It helps a great deal to be white. Every basic science department in my school cites diversity as one of its weaknesses. For a variety of reasons, it’s really hard to get to grad school if you’re black. I believe this to be mostly a failure of our education systems before grad school: basically, as a society we have decided to stop educating poor kids. My school makes a good effort to accept and nurture minority students. It just doesn’t get very many.

Those who do get into grad school have their schooling paid, get health insurance and a stipend of $30,000 a year or more. Postdocs make significantly more and starting salary for a beginning faculty member is north of $100,000, plus a start-up package of half a mil or more to get your lab going. Science is full of rich prizes, for best student paper, best article in a journal, best investigator under 40, best woman scientist, lifetime achievement, and so on: these can range from a few thousand to a million dollars. The prize money comes from professional societies, which run mainly on dues from scientists, and from private companies interested in developing science. In short, scientists have money to throw around.

Giving money “to ALS” feels good, but what does it actually buy you? Say a scientist has a gene or a protein and she thinks it’s the coolest thing since canned beer. But to work on it, she needs money. So she scans the grant opportunities and finds a disease she can plausibly link to. Let’s say it’s ALS. She dolls up her little geeky research project in a little black dress and stilettoes, with an up-do and some lipstick, hits “Submit” on the NIH website and sits back and waits for half a year for her funding score. The budget cuts mean that the funding cut-off moves down a few points, say from 25 to 20. Her application has to be in the top quintile to win. The ice bucket money, though, means she can apply to the ALS Association and have another chance. It effectively raises the cut-off again, back to 25 or even 30. That’s the impact of all this feel-good pop charity—a few percentage points on the funding cut-off.

The standard argument is that research needs to move forward as fast as possible: more grants=faster cure. That’s not obviously true. I’m not aware of any studies that examine that hypothesis; it’s simply taken as self-evident. If it is in fact true, the effect will probably be small. It is unlikely to bring new people into science. Most of the extra funding raised by the ice bucket challenge will go to people already working on ALS-related research. And again, as tragic as ALS is for those who live with it, it’s not the most dire medical issue facing us today.

*

For all these reasons, I’m interpreting the ice-bucket gimmick as a general challenge to give to a worthy charity. It’s so easy to forget to give back to the community. We’re all struggling financially in our own way, so we forget how rich we are in the bigger picture. All these ice buckets reminded me of this. I’m hardly rolling in dough, but I can find a hundred bucks. So while Sarah Palin and Patrick Stewart and everyone else is apparently writing checks to ALS, I gave $100 to the East Baltimore Community Development program of the Living Classrooms Foundation.

Baltimore, a city of 620,000, has a poverty rate of 25%. That’s about 150,000 people. Take the bottom quarter of them and you have more people in truly grinding poverty in one city than have ALS in the entire country.

And best of all, there is already a cure for poverty: money. Money well spent, of course—on education, nutrition, counseling, childcare, transportation, career guidance and training. My C-note could buy lunch for 20 kids. It could buy chalk for a hundred classrooms. It could enable a single mom to take the bus to work for a month. If transparent, responsible, effective non-profits like Living Classrooms had $40 million, they could lift an entire neighborhood out of poverty. That would mean less gun violence, fewer murders, less drug use, more economic development for my city. Maybe one of those kids will go to college, get interested in science, and apply to grad school.

So here’s my “ice-bucket” challenge: skip the bucket, let biomedical research take care of itself, and donate to an underfunded charity that will do some direct and long-term good.

You must be logged in to post a comment.