Here is the new ad from 23andMe that will begin airing shortly on cable TV*:

Genomics is going mainstream and the best news is first that it’s real simple and second that it’s all about me.

Let’s take the most obvious first: the “me” meme. Of course this relates to the company name, but the ad takes me to a new level. It makes “you” your DNA. I give them points for a couple of qualifiers — it “helps” make me who I am, one character says. But the overall message is that you are your genes.

It also exploits the meme of egocentrism. Nearly everything today seems to be all about me. Memoirs are the hottest genre of nonfiction. We have a magazine called “Self.” One of the most common themes on commercial websites is to have a “My [company name]” area, which usually just means they have your personal information to use to sell you more stuff. There’s even a “.me” internet domain, which they advertise “is all about you.” Who isn’t curious about himself? I’m the most interesting topic in the world! And 23andMe will tell me about my true inner nature for just $99.

One element of personalized medicine, then, is narcissism. Another, more noble, element is individuality. No one is more committed to his individuality than I am—but I’m also wary of its dark side: selfishness. I am struck by the single reference to future generations (“what I will pass on to my kids”). Again, this is a two-sided coin. In the Progressive era, the literature on genetic medicine emphasized family and community. There isn’t a hint of that here. On the one hand, then, the ad is free of the eugenic message of controlling human evolution. On the other, it’s relentlessly selfish. Most likely, the reason for staying away from issues such as family, community, and responsibility is that it enables them to steer way wide of abortion. This ad is about me, not my kids and not the future. That’s actually a new and rather radical development in genetics.

A persistent theme in popular literature from the 19th century to the 21st, is that hereditary information provides certainty. This despite the fact that one of the signal insights from genomics is how uncertain its results are. Genetic medicine today is all about probabilities, and to make informed decisions based on our genetics we have to understand how probability works. The ad works against this principle, promising certainty where there is only chance. “Now, I know” says one woman. No, you don’t. Now, you have a sense of risk—not certainty. This is a dangerous over-simplification.

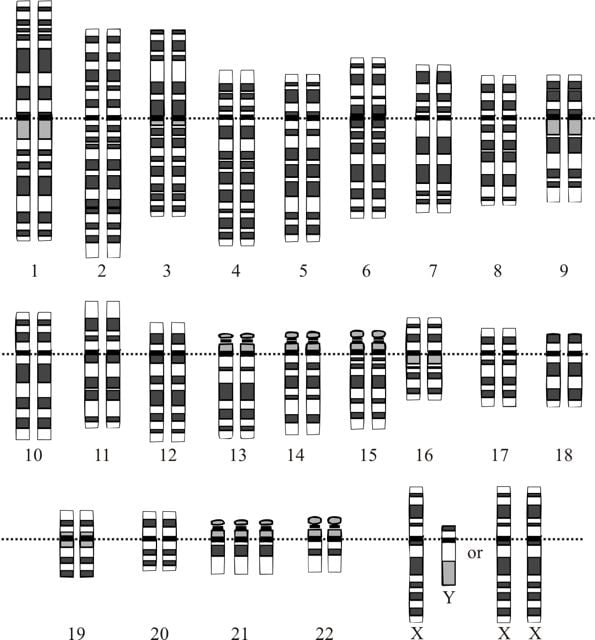

This sense of simplicity is also carried in the graphics. Note how there’s hardly a double helix in it. “Your” DNA is reduced to circles, dots, and lines. They move and whirl entertainingly and there’s just enough suggestion of complexity to carry the message that you can’t understand “you” without them‚ 23andMe. If DNA becomes as central to identity as companies such as 23andMe want to make it, this ad suggests that its iconic image may fade. Even the stripped-down ribbons and bars version is simply too complex for TV.

Most of the genetic “knowledge” promised is simple enough to be carried in the one- and two-syllable words that dominate mass-market media. Genetic medicine, stuffed as it is with Latinate and Greek words, is a tough sell in that market, but the ad pulls it off. At 0:21 we hear the longest word in the ad: “hemochromatosis.” The speaker pauses after the second syllable, to suggest empathy with viewers who get hung up on such terms. According to the Mayo Clinic website, hemochromatosis is indeed usually inherited, is rarely serious, is most common in men, and is the most common genetic disease in Caucasians. The ad script gives this word to a black man. Thus, one of the ad’s subtle messages is to erase racial differences—even differences supported by scientific evidence. It’s a commonplace in TV ads nowadays to feature men and women of many hues, but the 23andMe ad takes it a step further.

Another theme of the commercial is the way it suggests communities based around biological identities of health and disease. Once, our primary identities were with those who lived near us, or shared our work or hobbies or politics. But politics has become personal, our communities are digital, and our identities center around health. The sociologist Nikolas Rose calls this “biological citizenship.” The 23andMe website features forums where members who share particular mutations or risks can discuss diets, lifestyle habits, child-bearing decisions–or their pets, if they wish. They are communities based around health. The ad sends the message that race, class, and gender are no longer our defining social themes: what matters now is health and disability.

We hear so much about the importance of educating the public about their biology as a key component of contemporary personalized medicine, but in this ad that biology is reduced to bumper-sticker-like phrases about this circle “saying” I will have blue eyes and that line segment “saying” I have a risk of this or that disease. Learning about me will be fun, easy, and inexpensive. Thank goodness I can mail off a C-note, spit in a cup, and in a few weeks get a report that simplifies it all in language I can understand. The ad ends with a rainbow of people chanting “Me. Me. Me.” It’s the “Om” of the 21st century.

*h/t to Bob Resta for sending the link to the ad, and to Shirley Wu (@shwu) for a tweet that showed me that the hemochromatosis passage was too terse in yesterday’s version. I’d been wanting to add something about biological citizenship and Shirley’s comment suggested a way to do it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.