Colleagues, writers, readers, hear me for my cause…I come not to bury Watson, but to historicize him.

James Watson has not been in the news much in recent years. In fact, he has been lying low since 2007, when he said he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa,” because “all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours whereas all the testing says not really,” and was removed from the official leadership of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Prior to that, he had for decades been a staple of science gossip. No one has ever suggested that he embezzled money, cheated on his wife, or beat anyone up; his scandals have all been verbal. If there were a People magazine for science, Watson would have been its Kanye West.

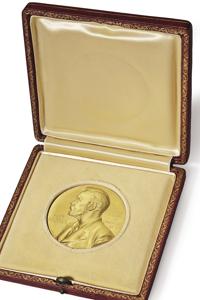

But last week, he was once again making headlines and enemies—this time with his auction of his Nobel Prize medal and the original drafts and typescripts of his Nobel speeches. The medal sold for $4.1 million, with another $600,000 for the documents. The event was a good deal more interesting than you might think.

Facebook and Twitter have been venting all week, the public’s ire only fueled by Watson’s public statements. In an interview with the Financial Times, Watson said several things that made right-thinking people go ballistic. (A link to this and a selective list of other major articles is at the bottom of this post.) He suggested he was financially hard up, as a result of being made a pariah since 2007. “Because I was an ‘unperson,’” he said, “I was fired from the boards of companies, so I have no income, apart from my academic income.” And yet, he wanted to buy art: “I really would love to own a [painting by David] Hockney,” he said. He iced it by insisting that he was “not a racist in a conventional way,” which sounds a lot like he was confessing to be an unconventional racist. Watson’s admirers buried their faces in their hands once again.

Watson, however, has not been the only one to thoughtlessly voice ill-considered views. In response, serious scholars expressed such nuanced positions as “Watson is a professional dickhead,” and “I no longer want to hear what [he has] to say.” “He’s a misogynist,” wrote one person on my feed. “…And don’t forget a homophobe,” chimed in another; “Yes of course,” replied the first, “I took that for granted.” Back-slapping all around, with much self-congratulation and smugness. That’s not analysis; it’s virtue-signaling.

The mainstream media hasn’t been much better. In Slate, Laura Helmuth achieved the trifecta of yellow journalism: inaccuracy, hyperbole, and ad hominem attack. Her article, “Jim Watson Throws a Fit,” asserted that Watson was “insuring [sic] that the introduction to every obituary would remember him as a jerk.” In her professional analysis, “he has always been a horrible person.” Always? I would love to borrow Helmuth’s time machine: I have a lot of gaps I’d like to fill in. Watson, Helmuth coolly noted, “knows fuck all about history, human evolution, anthropology, sociology, psychology, or any rigorous study of intelligence or race.” Serious academics whooped and cheered.

Helmuth, however, knows fuck-all about Watson; her piece is riddled with inaccuracies, rumor, and misinformation. Nevertheless, she exhorted Slate readers not to bid on the Watson medal. I admit I did follow her advice—and for the foreseeable future I’m also boycotting Lamborghini, Rolex, and Lear Jet.

Most surprising to me was the generally serious Washington Post. Like many people, I think of WaPo as a sort of political New York Times: tilting slightly leftward but mainly committed to high standards of journalism. But they headlined their article, “The father of DNA is selling his Nobel prize because everyone thinks he’s racist.” That sounds more like the National Enquirer than the Washington Post. Elsewhere, several articles referred to him as the “disgraced scientist” or “disgraced Nobel laureate.”

Watson-haters may jump down my throat for what follows, on the premise that I am defending Watson. Watson-lovers (dwindling in number, but still more numerous than you might think) may believe I fail to defend him enough. What I want to do is cut through the hyperbole, the ignorance, and the emotion, and attempt to do good history on a challenging, unpopular, and fascinating biographical subject. Watson has much to reveal about the history, the comedy, and the tragedy of 20th century biomedicine.

*

I have known and watched Watson for nearly 15 years. A year ago, I published in Science magazine a review of his Annotated, Illustrated Double Helix. I used the review to argue that in his treatment of Rosalind Franklin, Watson was conveying Maurice Wilkins’s view of her. In 1952-53, Watson scarcely knew Franklin, and later, Crick became good friends with her. Wilkins, however, hated her. The feeling was mutual and stemmed, at least in part, from lab director JT Randall’s bungled hiring of Franklin. Wilkins may well have been sexist, but probably not unusually so for his day. Ditto Watson and Crick. But in The Double Helix, Watson wanted to curry favor with Wilkins—his prime competitor and fellow laureate. The Double Helix is part history, part farce. It is naive to read it prima facie.

I had thought the review critical, but to my surprise and his credit, Watson loved it. He wrote me a personal note, saying that I was the first Double Helix reviewer who had gotten him, Wilkins, and Franklin right. (Against myself, I must note that Horace Judson was the first person to note that Watson and Crick’s principal competition in the Double Helix was not with Linus Pauling, but with Franklin and Wilkins.)

Based on the Science review, Watson requested me to write an essay for the auction catalogue. In addition to the medal, he was selling a draft of his Nobel speech and a complete set of drafts of his “Banquet” speech. A medal’s a medal; these documents were what piqued my interest. Since my current book project is on the history of DNA, it was literally a golden opportunity. Further, I would have unlimited personal access to Watson (he turns down most interview requests, especially from historians). I would of course be invited to attend the auction. In full disclosure, Christie’s naturally paid me an honorarium for my writing; I charged them as I would charge any private, for-profit company. Watson himself has paid me nothing.

When Christie’s broke the story of the auction, the press and the blogosphere pounced. Many people’s immediate reaction to the news was disgust, a sense that he was disrespecting the award. Two principal questions were on everyone’s mind. In formal interviews, public comments, and private statements, Watson obliged with a bewildering array of answers.

Why was he doing it?

- He needs the money. (“I have no income, apart from my academic income” [Financial Times])

- He is not doing it for the money (“I don’t need the money” [public remarks at Christie’s]). He doesn’t. The New York Times reports his annual salary as $375,000. He also has a mansion on Long Island Sound, an apartment on the Upper East Side, and other assets.)

- He wants to restore his image/polish his legacy (quite plausible)

- He wants to get back into the news (not entirely implausible)

- He is thumbing his nose at the scientific establishment (Slate). (Not only unfounded but ignorant. Science is one establishment he doesn’t want to thumb his nose at.)

What is he doing with the money?

- He wants to endow a fellowship for Irish students (from his ancestral County Cork) to study at Cold Spring Harbor.

- He will give money to The Long Island Land Trust and other local charities.

- He wants to give money to the University of Chicago.

- He wants to establish an HJ Muller lecture at Indiana University.

- He wants to give money to Clare College, Cambridge.

- His “dream” is to give Cold Spring Harbor a gymnasium, so that the scientists could play basketball (this would have required about $10M, he said after the sale).

- He wants to own a painting by David Hockney.

- He will keep some of the money.

Several observations immediately pop out of this. First, he plans to give away at least most of the money. Almost everything he has said involves charity, although in some cases (e.g., the Hockney—see below), this was not obvious. Most of these non-obvious gifts would go to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory—always Watson’s favorite charity.

Second, his eyes are bigger than his wallet. Reasonable estimates for an endowed lectureship are $250,000 and about $750,000 per student for graduate fellowships (http://www.gs.emory.edu/giving/priorities/naming_policy.html). A Hockney oil could cost more than Watson’s medal: they routinely fetch $7M–$8M (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2045824/Modest-British-artist-David-Hockney-74-worth-staggering-80-million.html).

On the Hockney, Watson said at the auction that in fact he “already had a couple of Hockneys.” He has a decades-long relationship with the artist, dating back, he said, to when Hockney offered to draw him, did so, handed him a print—unsigned—and then put the signed original up for sale. Watson laughed that he had to buy back the drawing he had been offered. He said he had no Hockney oils, however. But nor did he have any space in his house for a Hockney: his intention was to hang it in one of the Laboratory’s buildings. For many years, Watson has been decorating the Lab grounds with artwork. Reasonable minds may disagree about the need for a scientific laboratory to boast millions’ worth of art, but Watson wants Cold Spring Harbor to be a place of beauty and even luxury.

Third, it’s foolish to take his outlandish statements at face value. Most articles about the auction seized upon one of his remarks and presented it as “the truth” about what Watson thinks. That’s even worse than reading The Double Helix as straight memoir. Watson loves pissing people off—he may well have deliberately misled the media. Perverse, given the rationale of burnishing his image, but not for that reason ridiculous. He simply is not consistent. That inconsistency is something to explain, not brush aside.

Watson has always cultivated a loose-cannon image: having no filters has been part of his shtick. He has been observed deliberately untying his shoes before entering board meetings. But in his prime, he could usually filter himself when necessary. Nowadays, he keeps his shoes tied. Although he is clearly compos mentis, his ability to regulate his filters may have slipped. He’s always been cagier than he’s been given credit for, but his loose-cannon image is becoming less of an image and more of a trait. The quality he has nurtured, one might say, is becoming part of his nature.

*

Which raises the question: Is Watson merely a crank? Clearly, many in the science community believe he hurts the image of science and is best simply ignored. They treat him as an outlier, an aberration: someone whose views do not represent science or what science stands for.

I have a different view.

Granted, Watson is extreme in his candor; even his staunchest allies admit that he over-shares. But for both better and worse, he is emblematic of late twentieth-century American science. His lack of filters, not just over the past few days but over the last few decades, throws a harsh but clear light on science. He was there at the creation of molecular biology. Through his guileless but often brilliant writing, speaking, and administration, he has done as much as anyone to establish DNA as the basis for modern biomedicine and as a symbol of contemporary culture. He has helped reconfigure biology, from a noble pursuit for a kind of truth into an immensely profitable industry. Thanks in part to Watson, some students now go into science for the money. It has been said that in transforming Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory into a plush campus, filled with gleaming high-tech labs, posh conferences, and manicured grounds full of artwork, Watson made Cold Spring Harbor into a place where the young Jim Watson could never have flourished. The same can be said about his role in science as a whole.

The remarks Watson has made about women and minorities are emblematic of the late 20th century. His comments focusing on women’s looks rather than their intelligence are precisely the kinds of comments feminists have fought against since The Feminist Mystique was published, the year after Watson won the Nobel. Although such comments are thankfully much less tolerated than they once were, far too many men still objectify women. Once again, this is not to forgive his remarks; rather, it is to demand thoughtful explanation.

As to race: we are a racist society. From the time the first British and French landed on these shores, whites have condescended to and exploited every non-WASP ethnicity they have encountered: Native Americans, Africans and their descendants, Latinos, Asians, Jews, Irish, Poles, Italians. And many of those groups have then turned around and condescended to and exploited others. In his book of last summer, the New York Times science reporter Nicholas Wade wrote that anti-racism in this country is now “so well-entrenched” that we can afford to ask “politically incorrect” scientific questions about racial differences in intelligence. The current protests over police brutality toward black men in Ferguson, Missouri and Staten Island, New York, and elsewhere say otherwise.

Were Watson merely a rich old white guy who says retrograde things about race and gender, he could—and arguably should—be ignored. What makes Watson different is that he sees everything in terms of genetics–and not much else. In New York this week, he said that if one looked hard enough, one could find a genetic correlation with Baptism or with being a Democrat. One can probably find a “gene for” essentially anything. Genomic analysis is now so fine-grained, so precise, that the definition of “trait” is arbitrary. The problem is not that Watson is wrong about these presumptive correlations, but that it’s meaningless. The project of finding the genetic basis of everything has become too easy, too inexpensive, too powerful. His style of genetic determinism may again be more extreme than most, but his scientism (crudely, the belief that all social problems can be addressed with science) generally is common and becoming commoner.

Watson, then, shows us what happens when a typical man of the twentieth century thinks about genetics too much. James Watson is worth listening to, is worth understanding, because he represents both the glory and the villainy of twentieth-century science. He may not be easy to listen to, but neither was the viral video of Daniel Pantaleo choking Eric Garner easy to watch. If we shut our ears to Watson, we risk failing to understand the pitfalls of the blinkered belief that science alone can solve our social problems. Those who resort to simplistic name-calling do little more than reiterate their own good, right-thinking liberal stance. Doing so may achieve social bonding, but it gains no ground on the problems of racism, sexism, and scientism. Those who think the conversation ends with playground taunts are doing no more to solve our problems than Megyn Kelly or Bill O’Reilly. Calling Watson a dickhead is simply doing Fox News for liberals.

What is the corrective? Rigorous humanistic analysis of the history and social context of science and technology. Science is the dominant cultural and intellectual enterprise of our time. Since the end of the Cold War, biology has been the most dominant of the sciences. To realize its potential it needs not more, better, faster, but slower, more reflective, more humane.

I share the romantic vision of science: the quest for reliable knowledge, the ethos of self-correction and integrity, the effort to turn knowledge to human benefit. And at its best it achieves that. But science has a darker side as well. Scientific advance has cured disease and created it; created jobs and destroyed them; fought racism and fomented it. Watson indeed is not a racist in the conventional sense. But because he sees the world through DNA-tinted glasses, he is unaware of concepts such as scientific racism—the long tradition of using science’s cultural authority to bolster the racial views of those in power. Historians of science and medicine have examined this in detail, documented it with correspondence, meeting minutes, and memoranda. Intelligent critique of science is not simple “political correctness”—it is just as rigorous (and just as subjective) as good science. The more dominant science becomes in our culture, the more we need the humanities to analyze it, historicize it, set it in its wider social context. Science cheerleading is not enough.

The trouble with Watson, then, is not how aberrant he is, but how conventional. He is no more—but no less—than an embodiment of late twentieth-century biomedicine. He exemplifies how a near-exclusive focus on the genetic basis of human behavior and social problems tends to sclerose them into a biologically determinist status quo. How that process occurs seems to me eminently worth observing and thinking about. Watson is an enigmatic character. He has managed his image carefully, if not always shrewdly. It is impossible to know what he “really thinks” on most issues, but I do believe this much: he believes that his main sin has been excessive honesty. He thinks he is simply saying what most people are afraid to say.

Unfortunately, he may be right.

**

Here is a selective list of some of the highest-profile articles about Watson and the Nobel medal auction:

11/27/2014 “James Watson to sell Nobel prize medal he won for double helix discovery” (The Telegraph)

11/28/2014 “James Watson to Sell Nobel Medal” (Financial Times)

12/01/2014 “The father of DNA is selling his Nobel prize because everyone thinks he’s racist” (Washington Post”)

12/1/2014 “James Watson Throws a Fit” (originally titled, “James Watson is Selling Off His Nobel Prize: Please Do Not Bid On It”) (Slate)

12/02/2014: “Disgraced scientist James Watson puts DNA Nobel Prize up for auction, will donate part of the proceeds” (New York Daily News)

12/02/2014 “Jim Watson’s Nobel Prize Could Be Yours…For Just $3.5 Million” (Scientific American)

12/3/2014 “By Selling Prize, a DNA Pioneer Seeks Redemption” (New York Times)

12/04/2014 “Watson’s Nobel Prize Medal for Decoding DNA Fetches $4.1 Million at an Auction” (New York Times)

12/04/2014 “Watson’s Nobel Medal Sells for US$4.1M” (Nature)

12/05/2014 “James Watson’s DNA Nobel Prize sells for $4.8M” (BBC) [incorrect: their figure includes the “buyer’s premium,” i.e., the cut for the house]

I would prefer sclerose to sclerify, but forgiveness abounds. How much fun this has been to read. Herr Watson has the capacity to tie panties in a knot whether they be Fox or CNN.

I hadn’t heard “sclerose” used as a verb, but indeed it seems slightly better. “Sclerify” seems to be used more commonly with regard to plant cells; “sclerose” to animal cells. The intended image was hardening of the skin. I’ll change it. Thanks for the comment–and glad you enjoyed the piece.

“… scientism (crudely, the belief that all social problems can be addressed with science) generally is common and becoming commoner.”

“addressed with” is a critical ambiguity:

= informed by: yes. If not, which social problem cannot be better understood/ is fruitless to examine, with science?

= fully resolved with/ explained by: no, except for radical determinists.

This ambiguity bolsters the strawman that, since all science (ergo all scientists?) presumes to fully explain and resolve all phenomena, social included; hence it is obnoxious or at best misguided and therefore should be discarded on such issues.

Enter the nit-pitckers…

Scientism, more precisely, “an exaggerated trust in the efficacy of the methods of natural science applied to all areas of investigation (as in philosophy, the social sciences, and the humanities)” (Merriam-Webster)

You made your straw man out of whole cloth. Examine yourself: do you have an exaggerated trust in the efficacy of the methods of natural science applied to all other areas? If so, I hope to get you to reflect on yourself. If not, then I’m not talking about you.

well, thanks for dismissing my first thought about your conclusion as nit-picking.

i don’t think anybody with the slightest clue about what does and does not work in the pursuit of insight which has practical value would seriously contest the view that the scientific method is the best available tool – including in the humanities.

now, you may argue that the definition of scientism you used talks specifically about natural sciences. so what exactly are these methods of natural science which are inherently inapplicable to social sciences? where do you draw the line? i think at this point it is clear that *you* would be the one nit-picking if you actually tried to answer this.

now, if you replace “methods” with “models” in your defintion, we will get somewhere. it is evident that using quantum physics to explain society is a dead end. not because it would be inherently wrong, but because such excessive reductionism introduces a level of complexity which the human mind is simply unable to manage. on an individual level, the fundamental mistake of scientists like watson (or shockley, to name a much worse example) is the failure to recognize this, and not much more.

to me, the word scientism is the manifestation of everything that is wrong with the public’s perception of science (esp. in deeply conservative countries like the US), and by using it you directly pander to tribalistic impulses. just don’t.

This is an eloquent piece, and it does us a service by exposing some of the complications behind the vitriol. I’m puzzled, though, by the awkward stance that gives Watson the individual agency to reconfigure biology, but dismisses his sexism and racism as consequences of the larger culture. For consistency’s sake I would prefer either an assessment that represents him as a product of the broader scientific culture as well—i.e., the structure of DNA was ripe for the plucking in the early 1950s; DNA would have become the basis of modern medicine and biology would have been industrialized, Watson or no, etc.—or an assessment that also holds him to account for his individual perspectives on race and gender. In both instances he is emblematic of his context. Why credit him for the first and absolve him of the second?

A agree with the central point: that Watson is an excellent example of the need to humanize the sciences, and that we can’t do that if we villainize him. But I’m uncomfortable with being charitable to Watson to the point of rendering scientific culture subject to individual whim while at the same time toying with social determinism to excuse his faults. What’s good for the goose…

Thanks for your thoughtful comment. I will bear your remarks in mind as I refine my stance on Watson. Let me clarify, though: in no sense do I mean to absolve him. By saying he is typical I mean if anything to round up in the same pen others who are less explicit but equally complicit.

Saying someone is representative of a larger trend is not to dismiss that person as simply a product of the social forces in which he grew up. It is–or rather, I mean it–to use him as a lens through which to examine those forces. I’m interested in what Watson can tell us about the rise of biomedicine in the late 20th century. The growing preoccupation with the genetic basis of disease and behavior tends to magnify the prejudices and commitments of both scientists and the wider public.

As to the charge of social determinism…One of my principal concerns, as a scan of this blog’s archive will reveal, is genetic determinism. Reliance on any one variable (genes, environment, society, etc.) distorts the history; my aim is a textured account that synthesizes all of the most important causes. But of all the determinisms, I think genetic determinism the most insidious, because it tends to concentrate power among the elites. If then I err a bit on the side of environment and society, so sue me. 🙂

Thank you for this! I am so concerned at how ostensibly sober-minded scholars, some of them friends and colleagues, react with the vituperative self-righteousness, faux-dismissiveness (“I’m done with you – but first, more about your narcissism!”), and smug groupthink that you mention. It is as if aliens had temporarily possessed their bodies.

Atheist or no, the human animal seems to have a primal drive to create a devil, and as Thomas Mann said, if one believes in the devil, one belongs to him.

There also seems to be a primal need to erect pedestals, and then gleefully topple them with cries of “down with the supposed greats!” and “equality at last!” only to erect them again. Sometimes I think that people more readily condemn those with much in common with them for small flaws than those who are utterly opposed and completely different.

To those who say, “No gods, no masters,” I would also append this: “And no devils, no purges.”

Again, thank you for a thoughtful piece.

Thank you for the clarification, which is helpful. It was, I admit, unfair to characterize you as absolving Watson. Your explanation mitigates my worry, but doesn’t eliminate it entirely. I don’t object to a social determinist stance (or social determinist-ish stance, to give you credit for not being reductive about it) per se. Rather I think that either it should be applied consistently to both Watson’s politics and his science, or justification given for not doing so.

I’m on board with the suggestion that Watson’s social views frame a window into his social context. I’m just squeamish about placing this alongside a description of how important he was, individually, for driving change in biology. If we’re to err on the side of social determinism in explaining his social views, we should do the same with respect to his place in the scientific community. If not, we assume that scientific activity is somehow categorically different from regular human activity.

I envision two responses that might justify treating Watson’s place in science differently:

1. Although he’s typical of his social context, he’s atypical of his scientific context.

That is, we might say he’s among a class of scientists who have an unusually large influence on the field and we’re therefore justified in attributing more individual agency to his science than to his politics. I think this might work in some cases, but I don’t think it works with Watson. My (comparatively inexpert) take on Watson’s role in both the conceptual and institutional development of 20th century biology is that he served as a catalyst, accelerating it along an existing trajectory. DNA’s structure was certainly a game-changer, but it changed the game in a way that was consistent with existing large-scale trends. The industrialization of biology quite nicely mirrors the industrialization of physics, for instance.

2. Scientific context is different from social context. It changes in ways that favor the influence of individuals.

That is, we could argue that scientific activity is categorically different from regular human activity in some substantive way. We might say, for example, that since the scientific community is smaller than the society in which it is embedded it is more susceptible to perturbation by individuals. I’m skeptical about this tack, though, since it assumes a division between science and society that is more rigid than I would like. I don’t want to assume that those large-scale social forces stop at the laboratory doors.

We can legitimately disagree about the merits of either of these approaches (or some other approach I haven’t considered), but in any event it’s a case I’d like to see made. If it isn’t, it leaves the impression—unfair though it might be—that granting Watson his individual scientific and administrative accomplishments while placing his personal shortcomings in a bigger picture is overly charitable.

Now you see, this is why I like blogging. Sometimes you get truly thoughtful responses from random jet-ships.

My gut reaction is that I lean toward your door #1–his scientific achievements are extraordinary (even if/when not always honorable), while his social views are sadly ordinary (even though not universal). However, two caveats: extraordinary does not mean beyond reproach; and my views on him are evolving. Many Watson-haters want him to be one-dimensional and he’s simply not. I know that by complicating him I will be seen by some as exonerating him, but sensitive readers, I think, will see the difference.

That’s not to say the life and work should be treated independently. I see the task of the scientific biographer as integrating the life and the work into some sort of unified whole. Perhaps the most defining characteristic of scholarly history of science over the last 30 years or so is that it’s shown science to be a social act.

No doubt I will be more charitable to Watson than some would like—-and less so than others would like. But I do want to come across as exactly as charitable as I really am, and I do want to keep listening as I refine and expand my argument. I’ll bear your remarks in mind as I do. Thanks.

The price quoted by the BBC is correct – the buyer had to hand over $4.8 million to get the medal. The last 2 lines should read:

“12/04/2014 “Watson’s Nobel Medal Sells for US$4.1M” (Nature) [incorrect: their figure excludes the “buyer’s premium,” which the buyer has to pay in addition to the nominal price determined in the auction.]

12/05/2014 “James Watson’s DNA Nobel Prize sells for $4.8M” (BBC)”

While I think it is unseemly to discuss another person’s finances, since we seem to be at it, what has been missing from this discussion has been an acknowledgement of the very high cost of caring for a disabled child. We never really know what kind of money another person has, but a $375K salary is certainly not extraordinary, especially not in families where both members of the couple are at the end of their career and work at senior level jobs.

They say you need a million dollars to retire comfortably. The cost for caring for a disabled child for the rest of his life could easily be twice that. So, maybe he needs some money, or maybe all the money he has is tied up and he can’t do anything fun with it. But estate planning is costly and complex for any family with a disabled child. Calling him out on selling his medal because he has some other (albeit egregious) personality issues is tacky at best, and also cluelessly insensitive to other families in a similar situation.

A well written piece that lays bare some the entered. No doubt there are many who would literally burn Watson at the stake. Such racism to say people in one part of the world are not as smart as people in other parts of the world. Clearly racist as those people have darker skin.. Of course it is OK to say people of one part of the world are not as intelligence as people in another. As long as the less intelligent have “white” skin. It is an accepted truth that whites are not as intelligent as Asians.

Obviously someone who does not think like most others can not be tolerated in a diverse and tolerant society. There is no place for such heretical speech in a world of free speech. Science his no room for those who cite studies that lead to such unacceptable conclusions. Reproducible test results are not acceptable when the conclusion is not acceptable, scientific methodology be damned.

At one time the holy truth was that the universe orbits earth. How dare anyone contradict the truth! Heresy, he should have been burned at the stake even after he recanted. And there are those heretics who say man evolved from apes! Everyone knows the Bible is the literal truth. Since the Bible can not be wrong it is obvious that those fossils were put there by the devil to mislead believers. Just as how the studies of national IQ are products of evil to mislead believers. No need to show the data for Watson’s conclusions is wrong, like fossils it is a product of evil to mislead the weak.

Since it is impossible for people in Africa to be less intelligent then there is no need to find a solution. It is widely known that early stimulation improves IQ. But no need to provide programs to do that as these children can not be less intelligent. Nutrition also affects brain development before and after birth. But since there can be no difference in average IQ then there is no need for a food program. Despite the recognized need for both programs in the USA. It is impossible to fix a problem when the problem can not be recognized in today’s world.

An odd comment.

Agree with what I think you’re saying about sanctimonious, uncritical political correctness. Agree also about nutrition and brain development. No one says that differences in intelligence or IQ cannot exist, however. Disagree strongly with what I think you’re saying about the genetics of race being a legitimate scientific question. The reasoning is fairly subtle but rigorous. See my essay in Nature: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v513/n7518/full/513306a.html

I think genetics of a population is a legitimate subject. The population under review may be as small as a family tree or as large as a continent. Obviously it is very important to recognize that statistics do not predict the characteristics of an individual. Distribution of a given characteristic must be included, the median has little meaning without the distribution. For example a population with large variance in IQ means there are very intelligent members, disproving a racist stereotype. Research needs to be blind to prejudices and political correctness. Dr. Watson’s comments deserve to be reviewed not for the conclusion but for the data driving the conclusion. Books like “IQ and Wealth of Nations” and “The Bell Curve” should be critiqued for quality of data and thereby quality of conclusions. Not just the uncomfortable conclusions.

We abandon millions in the process of denying that differences exist. If genes for breast cancer are detected then surely preventive measures should be taken. If genes for aggression are detected should we not also take preventive measures? Or at least acknowledge the existence and the influence on a person’s role in society. For example the “Warrior” gene originally isolated among the Mauri people. In their culture being a warrior is a good thing. Recognition of that predisposition allows for constructive discussion of how to accommodate it in the larger society. Having the warrior gene is beneficial on the soccer field for example. It also fits well with law enforcement and military, the modern warriors.

Yes of course population genetics is a legitimate subject. My point is that the genetics of race is not a legitimate scientific question. Race itself is a heavily social concept. This can be true even though one may isolate alleles involved in the production of traits that we associate with race.

Similarly, the so-called “warrior” gene is a bit of real biology (the existence of a particular MAOA allele) embedded in social preconceptions. You point out the historical context of its isolation (in the Maori)–a group that is stereotyped as highly “warlike.” Had it been isolated in the Inuit it might have a completely different connotation. It might be the “risky decision” gene, say.

Mere data isn’t science. There’s always interpretation. I scrutinize those interpretations and point out the preconceptions and wider historical and social context in which they are made.

I’d like to be impressed by the show of reasonableness but I’m not. You belong to that vast army of compliant rationalisers with a weather eye on their employment prospects. I don’t criticise you for that but differential race characteristics are anything but ‘socially constructed’. It’s correct furthermore to emphasise ‘interpretation’ [your own being a case in point] given the political implications of truth-telling in our exciting new society. That is why the mob howls down anyone opposed to ‘anti-racism’ – a witch-hunt conducted exclusively against whites, naturally – and who chooses observable fact over self-serving, endlessly recondite ideological fine-tuning intended to protect research grants by reassuring the Emperor about the fit of his new clothes. Convince people truth-telling is an act of genocide or tantamount to advocating municipal gas-chambers and you’re free and clear of course, so I’m not saying hysteria doesn’t have its uses. I just wish people would drop the pretence of rational argument. There will never be a black Crick or Watson and you know it. Now I wonder why that might be….? Oh I’m forgetting: racism.

Grow up.

Well that was an amusing little string of non sequiturs. You think I write this blog to enhance my job prospects? Rational argument is merely a pretense now? Incoherent screaming is the only permissible form of discourse, then?

You are either a fool or a satirist; your writing isn’t coherent enough to tell which.

I want to thank you for this thoughtful article. I know Watson and am distressed that so much of the recent discussion of him in the news is so relentlessly negative (Helmuth’s article being the low point), although I understand it, at least to a certain extent. As far as his controversial comments on race, I think you get it (as well as everything else in your article) exactly right. Basically, if your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks a lot like a nail. Watson’s tool of course is the gene.

Watson, along with Rosalind Franklin, was a mere player when a couple of English scientists, (Crick & Wilkins), discovered DNA whilst at Kings College, London. Watson has been credited, somewhat tenuously, only because the Americans want(ed) to have credit for something more than inventing the Hamburger.

Stop talking about Watson!

BTW, “Your email address will not be published – ,yeah right!!! Hi Google & MS

Pro tip: Learn what the fuck you’re talking about, and THEN spout ridiculous nonsense. Works for me!

(PS Nina’s email is [email protected])

So much venting, so little substance.

Watson is correct. That hearing the truth raises the ire of those indoctrinated by political correctness is of no consequence to this.