[Edited, lightly, 10/30/18]

Well, I provoked another kerfuffle in the pages of Nature. And it’s a troubling one, because it suggests a widening culture gap between the sciences and humanities—a gap I’ve spent a quarter-century-and-counting trying to bridge.

The piece in question is my review of Robert Plomin’s new book, Blueprint. I want here to give some context and fuller explanation for that piece, without the editorial constraints of a prestigious journal.

Plomin is a distinguished educational psychologist, American-born-and-raised, who works in the UK, at King’s College London. I have nothing for or against Plomin. I and my editors at Nature worked hard to keep ad hominem attacks out of the piece. Plomin’s book, however, is terrible.

- “DNA isn’t all that matters, but it matters more than everything else put together” (ix).

- “Nice parents have nice children because they are all nice genetically.” (83)

- “The most important thing that parents give to their child is their genes.” (83)

- “The less than 1 per cent of these DNA steps that differ between us is what makes us who we are as individuals” (9)

- “These findings call for a radical rethink about parenting, education and the events that shape our lives.”(9)

I could go on—it’s teh Interwebs; people do—but you get the idea. However accurately he may represent the statistics, his statistics misrepresent the biology. With apologies to Benjamin Disraeli, there are three kinds of lies in genomics: Lies, damned lies, and GWAS.

*

Unless you’re some sort of third-rate hack, riding out your tenure on the strength of your rotation in a genetics lab in the mid-sixties, you know better than to say things like this. I presume that you, Gentle Reader, are not such a person. Plomin is not a hack scientifically, but as a writer he is. On the page, he is all exclamation points and pom-pons, thwacking the bass drum with his heel as he dances for DNA. DNA is everything. DNA is the Word. DNA is Love.

That’s a weirdly retrograde view in the postgenomic world. Again, see the above mainstream sciences. Either:

- Plomin is such a poor writer that he fails utterly to get across his putatively more nuanced understanding of the genome’s role in biology

- Plomin is a cynic, writing things he doesn’t believe in support of a repressive ideology that he does believe; or

- He is naive and genuinely doesn’t realize (or care) how this powerful new science is used.

I went with Door #3. As a reviewer of his book I took him at face value as a writer. I take him at his word when he says he is center-left, politically. (No conflict there with eugenic values. There’s a long tradition of leftist eugenics, back to the 19th C.) And I decided it would be unproductive to simply brand him an ideologue. Instead, I took the middle road, presumed innocence but naïveté. I gave him the benefit of the doubt in presuming innocence of intent, although I do think it an odd negligence on his part, given his express interest in using PGS to shape social policy. Seems to me that if you’re engaging with social policy you should be capable of thinking in terms of social policy.

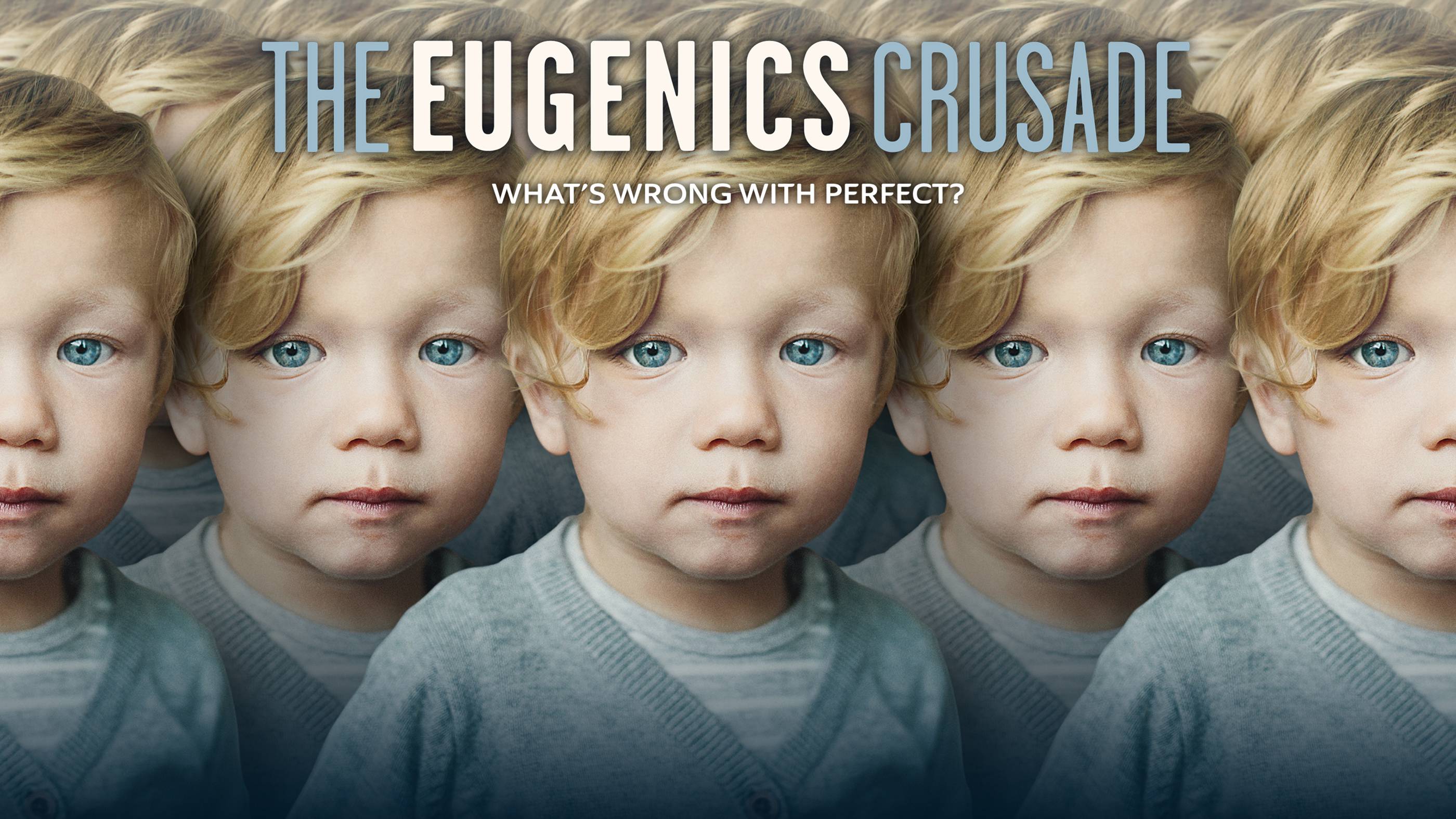

Why is it dangerous? Because it enables and encourages social policy of biological control. That shit scares me. And it should scare you. Plomin is so caught up in his DNA delirium that he says that environmental interventions toward human betterment are futile. Parents, teachers, government officials: Relax, there’s nothing you can do that really makes a difference. DNA will out. Kids will be what they will be, regardless, so don’t waste your money and time. Let’s take that apart.

*

First, short-changing environmental and GxE (genes-by-environment) effects in human personality is literally the entire point of Plomin’s book. I’m not talking about his published, peer-reviewed studies, I’m talking about his latest book. Nor am I damning all sociogenomics work—not by a long-shot. I am damning the simplistic message of this particular book: “DNA makes you who you are.”

Second, then, hidden agenda or not, Plomin’s argument is socially dangerous. Sure, genes influence and shape complex behavior, but we have almost no idea how. At this point in time (late 2018), it’s the genetic contributions to complex behavior that are mostly random and unsystematic. Polygenic scores may suggest regions of the genome in which one might find causal genes, but we already know that the contribution of any one gene to complex behavior is minute. Thousands of genes are involved in personality traits and intelligence—and many of the same polymorphisms pop up in every polygenic study of complex behavior. Even if the polygenic scores were causal, it remains very much up in the air whether looking at the genes for complex behavior will ever really tell us very much about those behaviors.

In contrast—and contra Plomin—we have very good ideas about how environments shape behaviors. Taking educational attainment as an example (it’s a favorite of the PGS crowd—a proxy for IQ, whose reputation has become pretty tarnished in recent years), we know that kids do better in school when they have eaten breakfast. We know they do better if they aren’t abused. We know they do better when they have enriched environments, at home and in school.

We also know that DNA doesn’t act alone. Plomin neglects all post-transcriptional modification, epigenetics, microbiomics, and systems biology—sciences that show without a doubt that you can’t draw a straight line from genes to behavior. The more complex the trait in question, the more true that sentence becomes. And Plomin is talking about the most complex traits there are: human personality and intelligence.

Plomin’s argument is dangerous because it minimizes those absolutely robust findings. If you follow his advice, you go along with the Republicans and continue slowly strangling public education and vote for that euphemism for separate-but-equal education, “school choice.” You axe Head Start. You eliminate food stamps and school lunch programs. You go along with eliminating affirmative action programs, which are designed to remediate past social neglect; in other words, you vote to restore neglect of the under-privileged. Those kids with genetic gumption will rise out of their circumstances one way or another…like Clarence Thomas and Ben Carson or something, I guess. As for the rest, fuck ’em.

These environmental factors are “unsystematic” in exactly the same way that genetic factors are: They do not act in the same way with every child. A few kids will always fall on the long tails of the bell curve: Some will do well in school no matter what you throw at them; others will fail, no matter what they have for breakfast. But the mean shifts in a positive direction. Same is true for genetics. That is literally the entire point of polygenic scores! Every single one of the many thousands of variables that shape something like educational attainment is probabilistic. Genes or environment, we’re talking population averages and probabilities, not certainties. There is no certainty—Plomin himself makes this point repeatedly (and then promptly jumps back on the DNA wagon). To venerate genetics and derogate environment on grounds of being “unsystematic” is at best faulty reasoning and at worst hypocritical.

Plomin is spreading a simplistic and insidious doctrine that says “environmental intervention is futile.” I don’t care whether Plomin himself, in his heart of hearts, wants to ban public education; he gives ammunition to people who do want to ban it. “Race realists” and “human biodiversity” advocates—modern euphemisms for white supremacy—read this stuff avidly. I watched them swarm around the discussion of my review on Twitter, many of them newly created accounts, favoriting tweets from my critics, saving those messages for later arguments.

“But does that mean that EVERYONE using PGS is a white supremacist?” people ask me, their keyboards dripping with sarcasm. No, dummies: It means it’s a risk. I’m giving you a qualitative risk score, a probability. Can’t you apply your own logic to other situations? Again, whether you critics are being disingenuous or naive, the effect is the same.

“So does that mean we CAN’T DO this science? Are you a fascist, trying to stifle scientific inquiry?!?” others gently query me. Again, no, dummies: I’m saying if you do this stuff, a) get your genetic bias out of the way and look at genes and environment, and b) be candid and explicit about your intentions and the risks of misinterpreting the data.

*

The last point I want to make is about historical thinking. A lot of critics said and called me things that initially puzzled me. I had no evidence, they said. It wasn’t a review that I wrote, they complained. I didn’t engage with the book but merely promoted my ideology, they protested.

Eventually it dawned on me: These people don’t understand historical reasoning. They fail to see a historical argument as being evidentiary! After all these years, I still find it surprising that people with PhDs should fail to acknowledge an entire branch of knowledge, a fundamental way of explaining the world. But okay, communication, not war, is what I’m after, so let me lay it out, at least as I see it.

By and large, experimental science explains the world in terms of mechanisms, more or less eternal and independent of time and context. Historical reasoning explains the world through the three C’s: context, contingency, and cause-and-effect through time. Context means that science doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It mattered that Nazi Germany arose after Progressive-era Americans had advanced a scientific program of sterilization and institutionalization of the defective. The Germans, sensing the power of rigid social control founded on scientific authority and finding that authority in American eugenics, modeled their infamous sterilization law of 1932 on Harry Laughlin’s “Model Sterilization Law” of 1922. Contingency means that it matters who did what when. Contingency says, “It could have been otherwise: Why did things turn out as they did instead of some other way?” And by continuity and change I mean that when a historian tries to understand the present in terms of the past.

In short, my review used historical evidence to put Plomin’s book in historical and social context, rather than scientific context, and a number of critics cried “Foul!”, failing to even see historical evidence as evidence.

It’s not foul when a reviewer examines the central claims and aims of a book—you all (critics) just aren’t familiar with the way I did it. Especially with a field such as sociogenomics, which defines itself as interdisciplinary and aims to shape society. You may not read Plomin’s book in social context, but it’s a legitimate and—as attested by the many plaudits I’ve also received for the piece—an important one. Learn your damn history.

Historical thinking is not anti-scientific. Darwin was a historical thinker par excellence. Evolutionary biology, cosmology, geology, paleontology—these are historical sciences. To reason historically is by no means to refute the scientific method. In fact, I would wager that no person can get through life without employing historical reasoning). To do so is to refuse to learn from experience.

Because I did not primarily use scientific evidence in my review, some misguided and uncritical critics peg me as a radical relativist. You got the wrong guy, pal. I studied sociobiology and neuroethology as science for years, under some of the greats. Radical relativists do exist in the humanities and social sciences—I argue against them all the time.

Others, like Stuart Ritchie, bash away at me boneheadedly, picking at details of the piece that make no difference to my argument without the slightest effort try to understand what I am in fact saying. Playing “gotcha” is easier than real debate, but it wins you points with your yes-friends, I guess. Sad!

Historical thinking pulls your eye away from the microscope to look at science as an enterprise evolving over time. For really abstruse sciences, doing so may be mostly an intellectual exercise. But the more social salience a branch of science has, the more important it is to take the long view once in a while. And when you’re explicitly advocating using your science to shape society, it’s incumbent on you to do so.

I identify with distinguished, politically alert scientist-critics like Jonathan Beckwith and Richard Lewontin, who have critiqued their science (even their own science!) in order to make it better. I believe that in science as in politics, dissent is the sincerest form of patriotism.

*

In short, I don’t think sociogenomics is wrong; I think it’s being done wrong, and written about wrong, by people like Plomin. Some people are doing it right. In a forthcoming piece in the MIT Technology Review, I discuss the work of Graham Coop at UC Davis. I won’t go into detail here, but for examples of honest, candid, historically sensitive discussion of PGS research, see this and this. This post is my attempt to do for my critique of PGS what Coop did for his own PGS research (which, for the record, I admire). By and large, I think the biologists have been doing better at avoiding deterministic talk than the social scientists like Plomin—although some social scientists, like the sociologist Dalton Conley at Princeton, do at least have complex positions worth taking seriously.

Plomin does none of this. Instead, he gives us a simplistic and distorted view of the role of heredity in behavior that causes much social mischief. We can watch some of that mischief in real time as the white supremacist trolls swarm around this debate like yellow-jackets around an open soda. Other risks we can infer from careful comparison with historical examples—looking at both the similarities and the differences between Blueprint and previous attempts to use heredity to shape social policy. The argument in Blueprint—that “DNA makes us who we are” and environment “is important but it doesn’t matter”—is an idea grossly wrong on many levels. It’s not supported by the evidence and it’s socially dangerous.

And someone’s got to call bullshit on it.

Like this:

Like Loading...

![[Blueprint cover]](https://genotopia.scienceblog.com/files/2018/10/Blueprint-cover-e1538767683839.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.