According to a recent study, pork appreciation could be genetic. Though the finding remains speculative, the correlation of such a high-level subjective character trait with a particular gene is already having a far-reaching impact on domestic policy.

In the study, variants of the OR7D4 gene, which encodes an odorant receptor, were correlated with a preference for pig meat. Subjects who possessed the RT allele rated the appeal of pork more highly than those who possessed a variant called WM. The gene in question responds to the steroid androstenone, which, it turns out, is present in high amounts in the muscle of male pigs. The authors simply connect the dots and suggest that the taste for pork may be mediated by this gene. The paper was published this week in the journal PLOS One.

This study represents a breakthrough in the genetics of breakfast. For years now, researchers have searched in vain for the gene for crispy potatoes, tender inside, with onions, bell peppers, salt, pepper, and a little oregano. An egg-hunt for the Over Easy Gene has flopped, the candidate-gene approach providing exactly zero gene candidates. The scientific community was buzzed, however, by the discovery of two coffee genes in the spring of 2011.

The Pork Board, American Home Fries Association, Egg Board, Florida Citrus Growers, and Coffee-Growers’ Association are joining forces and lobbying direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies such as 23AndMe to create a Breakfast Panel in their personal genomics profiles. Researchers and marketers hope to identify a genotype for the preference for an “American breakfast.” Preliminary studies suggest that a still-hypothetical “Continental” genotype shows linkage between a preference for a nice buttery croissant or currant scone with cigarette smoking, universal healthcare, promiscuous sex, and tight pants with pointy little effeminate shoes. Dick Dorkins, who heads up the personal genome sequencing effort “Project Dick,” has already assembled such a hypothetical panel and run it against his own genome. He claims that his sequence shows that he is as American as the gene for apple pie.

These findings raise the possibility of prenatal genetic diagnosis and selective abortion. The prospect of implanting only embryos genetically tailored to like Mom’s cooking may be too tempting for farsighted prospective parents to pass up. In the not-too-distant future, only “foodies” may have gastronomically adventurous children, while those for whom salt is a spice may be able to tailor their progeny to share their lack of taste. Vegetarians could become a separate caste and sent to a reservation in Northern California, where their only sustenance would be mung beans and marijuana.

This naturally has political implications. Indeed, the conservative pro-science group Freedom Control Institute issued a white paper yesterday recommending genetic screening for health, genealogy, and breakfast preference for all presidential candidates in future elections. Under their plan, a Breakfast Panel profile would be used to screen anyone seeking to occupy the highest breakfast nook in the land. Any candidate showing a Continental Breakfast Profile, with variants such as OR7D4-WM, would be ineligible to be included on primary ballots in Kansas.

The idea is not without controversy. Questions remain about where one would draw the lines around a properly free-market American breakfast. Watchdog groups decry the amount of pork in American politics, yet it seems unrealistic to do more than trim some of the fat. Presumably the sausage-links gene variant of OR7D4 would qualify one for office. But what about Canadian bacon?, asks Dorkins. Is that even bacon at all?

Then there is the whole matter of toast. Right-wing genetic hardliners insist that true Americans eat only white bread, while moderates point out that six out of the last six Presidents have eaten wheat toast. Possession of a pumpernickel variant, all sides agree, would indicate a dangerously Euro-socialist culinary constitution and should debar someone from higher office.

The dairy lobby, which so far has been left out of these discussions owing to low blood-sugar, has begun to push for social policy on the genetics of preference for milk products. Cheese, for example, has long been a political hot potato. Hardliners favor limiting candidates to cheddar and colby. Rallying around the slogan “Soft on cheese—soft on defense,” they argue that a strict “No Brie” genetic policy is a bulwark against socialized medicine. Opponents, however, accuse them of lactose intolerance, pointing out that the high correlation between the genetics of preference for hard and soft cheeses would make such a policy impractical.

Such self-styled “lactose liberals” suffered a blow last week, when a Colorado woman spilled her yogurt on President Obama. With one flick of her spoon, she disabused the President of what had been a pro-active culture stance. Within hours, the Oval Office issued the “Yoplait Doctrine,” which severed diplomatic relations with any nation producing dairy products containing live bacteria intended for sale in the United States. More than 40 countries, including India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Germany, and even neutral Switzerland, immediately closed their American embassies.

A global food fight may be beginning that could trigger the Broccoli Clause of the 1992 Paris Convention on food policy. If invoked, all participants would be required to eat their vegetables or else be sent to their rooms without any dessert.

Like this:

Like Loading...

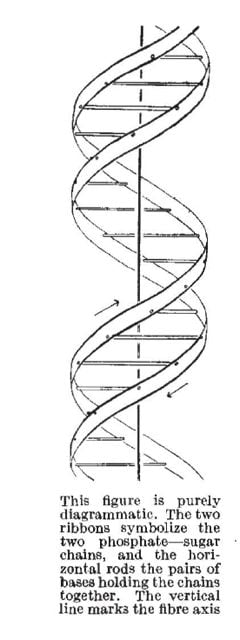

Why astrobiology? My next project is a biography of DNA. One key part of the book will be the story of how we’ve come to understand the origins of DNA and the origin of life in an RNA world. So I’ll be using the unparalleled resources of the Library to write the history of origins research since the genome project, as well as working on the rest of the book.

Why astrobiology? My next project is a biography of DNA. One key part of the book will be the story of how we’ve come to understand the origins of DNA and the origin of life in an RNA world. So I’ll be using the unparalleled resources of the Library to write the history of origins research since the genome project, as well as working on the rest of the book.

For those up to the challenge, the park promises to get your pulse racing. At any moment, Benito Mussolini, Josef Stalin, Idi Amin, Pol Pot, or even Hitler himself may pop out from behind a tree and attempt to

For those up to the challenge, the park promises to get your pulse racing. At any moment, Benito Mussolini, Josef Stalin, Idi Amin, Pol Pot, or even Hitler himself may pop out from behind a tree and attempt to

You must be logged in to post a comment.