Here’s the cover art for my book!

This is also logged on the Science of Human Perfection page in the title bar.

Month: March 2012

The biology of good and evil

In today’s New York Times, columnist David Brooks writes about the innate capacities for good and evil. Criticizing what he considers the prevailing worldview today, he writes that we believe that nature is fundamentally good, and hence, so we believe, are people. The Hitlers, the Idi Amins of this world are fundamentally warped. “This worldview,” he writes, “gives us an easy conscience, because we don’t have to contemplate the evil in ourselves. But when somebody who seems mostly good does something completely awful”–such as Robert Bales‘s recent massacre of 16 Afghan civilians, including children–“we’re rendered mute or confused.”

Brooks prefers an older view, in which humans are believed to be a mixture of good and evil. Thus, everyone possesses in some measure the capacity for atrocity. We should be concerned and shocked when such actions are committed, but not surprised. So far, I’m with him. I agree about the “easy conscience” that comes with the lack of hard introspection.

But Brooks then makes his argument biological. He cites the University of Texas evolutionary psychologist David Buss in support of his view. Buss studies human behavior such as jealousy, violence, and mating strategies in the context of Darwinism and especially sex differences. He is thus part of a long tradition of psychologists who seek to explain sexual and antisocial behavior in naturalistic terms, stretching back through Edward O. Wilson‘s sociobiology in the 1970s (here is the famous “Chapter 27” from his textbook, which defined the field) and 1980s, to Progressive-era researchers such as the feeblemindedness expert Henry Goddard, the founder of eugenics Francis Galton, and the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso. Such work inevitably sparks controversy because it claims that antisocial behavior is innate and therefore genetic.

Genetic determinism is often associated with a conservative and punitive worldview. If violent tendencies are inborn, there is little we can do about them. Those who display them must be locked up, so that the law-abiding can get on with their lives. Genetic determinism tends to ignore the environmental causes of violence, such as poverty and oppression. Historically, it has tended to align with the preference for criminalization over medicalization of antisocial behavior. That, however, may be changing. Perhaps it is possible to “cure” such behavior by tweaking our genes.

In “The Murderer Next Door: Why the Mind is Designed to Kill,” Buss argues that murderous tendencies have been selected for in evolution. By definition, that which can be selected for has not only a basis in our physical bodies, but therefore a basis in our genes. A necessary implication of this view, then, is that there are certain forms of certain genes that predispose us to violence. Buss’s work is the evil twin of works such as Matt Ridley’s The Origins of Virtue. Although the eugenics of the 1910s–1930s is easily mocked for its simplistic biologically determinist analyses of complex behaviors, now we have more complex biologically determinist analyses of complex behaviors. The problems raised by both are essentially the same.

If there are genes for good and evil, then we can find them. Genome-wide association studies are certainly capable of finding correlations between murder and certain passages in our DNA text. I believe they can find correlations between DNA and almost anything. It is only a matter of time before the “genes for” heinous acts such as Bales’s are found.

I believe those genes exist. There is no rational reason to doubt it. The problem is that the finding may well be meaningless. Something like criminal behavior is so complex that it will turn out to be influenced by hundreds if not thousands of genes. Those genes will interact in complex ways, both with each other and with the environment—and those interactions will themselves depend on other genes and other environmental factors. Finding genes associated with violence would be like finding a handful of sand and claiming that a cause of surfing has been discovered. Well yes, but so what?

Historically, finding that violence is “in the genes” has reinforced punitive models of behavior modification. “Innate” has equaled “immutable.” But biomedical research is moving rapidly toward being able to change the genes. In principle, the controlled environment of the laboratory is much more conducive to engineering than the messy world of populations, culture, and economics. Someday, we may wish for a trait to be found to be strongly heritable, for then it will be easy to alter–the way infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, which once were a death sentence, are now in the age of antibiotics easily treatable. In such a world, the ultimate arbiter of social behavior shifts from the justice system to the biomedical system.

Such a biomedical Brave New World would have enormous implications. I don’t see that we have begun to address the consequences of such a shift.

The Science of Human Perfection

I’ve started a new page–it will stay in the header bar above–for my forthcoming book, The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine, due this summer from Yale University Press. The book is a history of the promises of genetic medicine, from the late 19th through the late 20th centuries. It shows how genetics went from being a backwater of agricultural science to the core of biomedicine. Eugenics, I find, was not a hindrance to genetics going medical, but the vehicle by which it went medical.

I’ve posted a link to the Preface, and will post news about it there as it comes in. Enjoy!

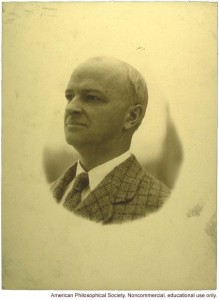

Who’s Laughlin Now? Exclusive Interview with Expired Eugenicist Extraordinaire

Not long ago, Genotopia received a comment from Dr. Harry H. Laughlin, a noted eugenicist. This surprised us, because Laughlin died in 1943. Unsure whether he is visiting us from the spirit world or simply undead, we nevertheless fearlessly seized the opportunity to request an exclusive interview with him, which he kindly granted. Well, perhaps kindly isn’t quite the right word…

Harry Hamilton Laughlin was a principal architect of the American eugenics movement from 1910 to 1940[1]. Born in 1880 in Oskaloosa, Iowa, he worked as a high school teacher and principal before being tapped by Charles Davenport to run the new Eugenics Record Office, founded in 1910 at what is now Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, on the north shore of New York’s Long Island. Laughlin built the ERO into the epicenter of American eugenics, training “fieldworkers,” collecting pedigrees and other family data, publishing articles both scientific and popular, and lobbying on behalf of the need to prevent the reproduction of the “unfit”—the diseased, the infirm, the antisocial and immoral, and especially the feebleminded, a broad term that could include all forms of subnormal intelligence but which was often applied to those of near-normal IQ. He was a staunch advocate of sterilization, institutionalization, and birth control as means of limiting the numbers of the socially undesirable. In 1922 he drafted a “model sterilization law” that became the basis for California’s sterilization law and which in turn informed the 1933 sterilization law in Nazi Germany. In 1936, Laughlin proudly accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg, a gesture of recognition by Hitler’s Germany of Laughlin’s contributions to eugenic health. Once an inspiration to eugenicists across the land, the ERO sank in reputation through the 1930s and became an embarrassment. The Carnegie Institution of Washington, which administered the Office, shut it down at the end of 1939, sending Laughlin into retirement. He died on Jan. 26, 1943, in Missouri, with his wife Patsy, but childless and with epilepsy. His thanatography will have to await future scholarship…

GT: In the first decades of the twentieth century, you made your reputation as perhaps the nation’s foremost opponent of feeblemindedness. Explain feeblemindedness for us, would you? Why did you see it as the root of so much social evil?

HL: The nation’s foremost opponent of feeblemindedness? Is anybody in their right mind a proponent of feeblemindedness? Let me make it simple for you – feeblemindedness is genetically determined low intelligence. With it comes all the social woes of the inferior classes and races. Inferior minds produce inferior morals, inferior habits, inferior looks, and feckless breeding. And the broods they produce – well, with your genetics background you should know that like produces like. It’s a menace to us all. Society just spirals down the porcelain canyon and flushes out into the Vale of Siddem. The solutions are simple – stop the feebleminded from breeding. You can’t fix their brains, but you can “fix” them other ways. And we must keep the inferior races out of the country so the Great Saxon Stock of this country is not overwhelmed. I don’t know why you can’t see that point, Genodopia. Any bright mind would.

GT: That’s –TOpia, ahem. Is feeblemindedness still a problem now, in the early twenty-first century? If so, how—and what should we be doing about it?

HL: Is it still a problem? Is that a serious question? This has become a country of immigrants from the lowest races – Africa, Asia, Mexico. Do you know that in a few decades, whites will be a minority? A MINORITY? Do you think that mass of defective germ plasm will be able to put a man on the Moon or make great medical discoveries? You can’t make great achievements when you aren’t smart enough for high school and spend your life collecting welfare checks.

We might still be able to reclaim this country if we are willing to take drastic measures, the same ones I proposed a hundred years ago. Strict immigration control – we only grant citizenship to the whitest and the brightest. We clear out the illegals who are already here. And for the rest, there is the Sharp Solution. Pay them to be sterilized. God bless Harry Sharp.[2]

GT: Ouch. Not long after your death, Sheldon Reed of the Dight Institute for Human Genetics in Minnesota coined the term “genetic counseling.”[3] He did so in part to differentiate “nondirective” genetic advice from the sometimes-coercive methods you and your colleagues employed in your eugenic program. In recent years, however, we have seen a backlash against nondirectiveness in genetic counseling. Do you see this as a positive development?

HH: Sounds like a bunch of double-talk to me. Reed was at heart a eugenicist. He just thought that if you laid out the facts for parents they would choose not to have a feebleminded kid. Nice Guy Eugenics. It was doomed to failure because Reed missed a basic point – feeble minds cannot understand complicated information. And even if they could, their unbridled enthusiasm for sexual intercourse would not let them refrain from producing broods. Reed was nudging, but successful eugenics calls for shoving. This is Genetic Warfare, my friend.

GT: That really is strikingly modern-sounding.

HL: And as I understand it, this nondirectiveness is just a bunch of psychology mumbo-jumbo. The backlash against it is the wrong kind of backlash. These new genetic counselors think that their patients have no responsibility to society, only to their own private lives. Well let me tell you, making babies is a very big public responsibility, and genetic counselors need to tell their clients that society does not need any more problems than it already has. That’s the right kind of backlash against nondirectiveness (what a ridiculous term!).

GT: Makes you wistful for the good old days before Nuremberg, doesn’t it? Where do you see hope for eugenics today? What’s going on in human genetics that gives you satisfaction?

HL: I sure wish we had this technology back in the day. The newspapers are filled with stories that link these genetic discoveries to crime, depression, alcoholism, political beliefs, moral failings.

GT: Even the gene for thalassophilia, which your boss was so ridiculed for after both your deaths, has been found.

HL: This is exactly what all the ERO pedigrees showed, but now there is hard biological proof. The DNA evidence is so overwhelming that people will have to see the eugenic light. And I understand that pretty soon we can all have our entire genetic blueprint scanned for a few well-spent dollars. We can start incorporating this genetic sequencing into every aspect of society – in marriage, in assigning children to the proper educational tracks so we don’t waste money trying to make gold out of lead, in deciding who can immigrate into the country, in getting people on the right career tracks, in tracking criminals before they commit crimes…. we have the possibility of a Galtonian Utopia within our grasp.

GT: An old saw of your day was that eugenics was “the self-direction of human evolution.” Are we closer to that goal now, in the early twenty-first century? Do you think we will ever truly achieve it?

HL: We can – we MUST – direct our evolution. Otherwise we face a genetic and evolutionary implosion, a return to a race of brutes cowering in caves, frightened of the dark. Nuclear nightmares look like pleasant dreams in comparison.

GT: You are a religious man, are you not? Isn’t playing God a game for atheists? How do you reconcile “playing God” with your God?

HL: God wants us to live to our full potential, to be more God-like, to be in his image. Do you think God looks like a Juke [4] or a Dugdale? That is why he gave us these great gifts of intelligence and wisdom and morals. Only with wise breeding can we be in God’s image. Eugenics is not “play”, my friend. It is a theological imperative.

[1] Philip K Wilson is working on a full-length biography of Laughlin. He has been a great help to me in framing the questions for this challenging interview. See “Harry Laughlin’s eugenic crusade…” for more insightful analysis of Laughlin. See also Dan Kevles’s In the Name of Eugenics

[2] See Elof Carlson’s and Jason Lantzer’s chapters in Paul Lombardo, ed., A Century of Eugenics in America (2011)

You must be logged in to post a comment.