“We have found the secret of life!” So Francis Crick exclaimed, bursting into the Eagle pub in Cambridge, exactly sixty-one years ago. He and his partner, James Watson, had just solved the structure of DNA. The only eye-witness account is from the historical farce The Double Helix, written more than a decade after the fact by Crick’s number one fan, Watson. There is much in the book that cannot be taken at face value, as I suggested in my book and in a recent review in Science. But let’s take Watson at his word here. Because whether or not Crick in fact uttered that famous sentence, the anecdote rings true. For one thing, it concisely conveys the thrust of Watson’s career since 1962, the year he, Crick, and Wilkins went to Stockholm. For more than half a century, Watson has been DNA’s chief spokesperson, literary agent, and cheerleader. Whether or not Crick said it, Watson said it, and it’s fair to say that no single person has done more than he to promote the idea that DNA is the secret of life.

Sixty-one years after the double helix turns out to be an interesting moment in the history of heredity. My guess is that the early 21st century will turn out to have been an inflection point. For the last, oh, couple thousand years, “hereditary” has connoted “innate.” It was that part of you that could not be changed. That’s changing, and yet our culture has not yet caught up with DNA science. In 2014, the double helix is simultaneously reinforcing and undermining the idea that your genes are your immutable identity. The meanings of DNA are multiple and sometimes contradictory.

*

“We have found the secret of life.” The statement is profound yet untrue. It is a marvelous reflection of one of science’s greatest deadfalls: thinking constantly about a particular mechanism tends to make one think that it’s the key to the universe. It should be self-evident that there is no single secret of life. Heredity is obviously important—evolution can get no traction without it—but the secrets of life include metabolism, self-organization, homeostasis, reproduction, adaptation to the environment, and response to stimuli. DNA is involved in all of those processes, but it’s a mistake to think it fundamental to them. Not a mistake, actually: an artifact.

The double helix reinforced the idea that heredity lies at the heart of life. I’ve written a lot about hereditarianism here, so won’t rehearse those arguments again. Suffice it to remind you that the development of Mendelian genetics after 1900 gave a big boost to hereditarian thought and put fangs on the Progressive era eugenics movement. Eugenics has two central ideas: your genes are the most important determinants in making you who you are; and we must take control of our own evolution. I maintain that the former is wrong and the latter is inevitable.

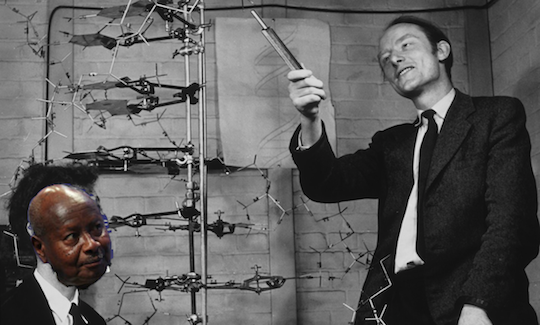

After the 1962 Nobel Prize to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins, the double helix became the emblem of the “new genetics,” or molecular biology. Like Mendelism 60 years before, it prompted a new way of thinking about how to control our evolution. Now that we understand how genes actually work, scientists began to think, we no longer need to rely on crude measures of controlling bodies through marriage restriction and sterilization. We will be able to do it delicately, surgically, through targeted modification of the genes. The year after Watson, Crick, and Wilkins won the Nobel, the polymathic biologist Joshua Lederberg fantasized about just this, and through the 1960s conference after conference debated the scientific, philosophical, and religious problems entailed by the prospect of directly manipulating an individual’s hereditary makeup. Early gene cowboys such as Stanfield Rogers and Martin Cline circumvented both the rules and the principles of research ethics in their zeal to perform “genetic surgery.” In short, as soon as DNA became popularly acknowledged as the secret of life, the nature of heredity began to change. The first cracks appeared in the monolithic concept of heredity as the immutable part of human identity.

Of course, a few cracks in the glaze don’t prevent a pot from being used. DNA science has been enormously productive. The more we study DNA, the more central to life it seems. And it has had fantastic PR. Thanks to the tireless efforts of Watson and others, the elegant twisting ladder of the double helix became the most recognizable scientific image since the Bohr atom. Niels Bohr’s famous image of a nucleus with three orbiting electrons signified not the science of quantum mechanics that it helped launch but the atomic age that began some four decades later. It was the cultural, not the scientific, connotations that gave the image its, pardon the expression, valence. Ditto the double helix. Fantasies about engineering the genome notwithstanding, in the popular imagination DNA became a secular stand-in for the soul: it represented our essence, our identity, our nature.

Since the turn of the century, though, two forces have been working at cross-purposes. On the one hand, biomedicine has become absolutely DNA-centric. Every branch of the life sciences, from paleontology to ecology to cardiology is grounded in the idea that the genes are not just important but fundamental to life. The idea is so entrenched it seems almost ludicrous to question it: life springs from the nucleus. The chromosomes contain the genes that make the proteins that make us who we are. No matter where you start, if you plumb the depths of biological causality, ultimately you arrive at the core of being: the DNA.

And yet. If you press scientists—hell, if you simply read the scientific literature—evidence abounds that that view is dissolving. The DNA is increasingly understood not as the bottom of the causal hierarchy but as a node in a network; dynamic, contingent, and susceptible to influence. It can be read in an almost infinite variety of ways. Its products—proteins and RNA molecules—can undergo modifications that dramatically change their function. At the frontiers now are new techniques such as CRISPR-cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, with cas-9 enzyme), which permit the editing of DNA sequence, as a copyeditor might scan a manuscript repairing typos. The first genetic engineering involved the manipulation of whole intact genes from organism to organism. Now the dream is to simply go in and repair—or improve—an individual’s genome, nucleotide by polymorphic nucleotide.

The inflection point, then, is the change from thinking of DNA as that which is innate and unchangeable, to precisely that which is changeable. Thanks to the billions of dollars of public and private money poured into high-tech biomedical research, changing the DNA is becoming more practical than changing the environment. It is beginning to seem more feasible to treat obesity by changing the genes (or their products, the proteins) rather than by changing the diet. It is beginning to seem more practical to treat crime by changing the genes rather than address the tangled social problems of the inner cities. DNA can be treated in isolation. It can be controlled. Changing the genes is technically hard but conceptually simple; changing the environment is technically simple but conceptually hard. Humans are better with their hands than their minds.

So here we sit at the crossroads. In the labs, DNA is increasingly manipulable. It has shed its reputation as that-which-cannot-be-changed. But in popular culture, the double helix still stands for innateness. DNA can be edited, but “DNA” remains immutable. Notwithstanding the mountains of evidence that show genes and environment to be interpenetrating and mutually contingent, we continue to fall back on a simplistic nature vs. nurture concept. And so we “blame” our genes for any quality we cannot or will not change.

Thus we arrive at last Valentine’s Day (of course), when a savvy PR person released the results of a study suggesting that “a gene for homosexuality” lies on the long arm of the X chromosome. Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, may be retrograde but he reads the science news. Having promised to outlaw homosexuality, yesterday he backpedaled, saying he was turning to scientists for guidance . Apparently the Valentine’s gay gene gave him a pang of conscience. He said that if homosexuality is “learned it can be unlearned.” Being straight is, for him, a matter of personal responsibility. However, if anyone can show him a gay gene, he might reconsider signing the bill. If homosexuality is innate, it’s not your fault if you are gay. Ironically, on this Museveni is on the same side as the gay community. From Kampala to the Castro, we persist in thinking that if it’s in your DNA, it’s not a moral issue. I understand the politics of the American gay community’s insistence that gayness is inborn, and perhaps it is indeed the expedient course in this political climate. But in Germany, gays insist that homosexuality is not inborn, because they have a cultural memory of a time when the solution for an innate “pathology” was extermination. The valence of scientific evidence is not inherent; it depends on the time and place.

Gayness is neither a unit character, like white eyes in Drosophila, nor can it be labeled either genetic or learned. Like anything else interesting, it is a graded behavior, sometimes inborn, sometimes learned, the result of a vast constellation of genes and environmental factors whose relative roles are themselves mutually contingent and shifting. You can find dozens of genes that correlate with it, I’m sure. Some will be associated with it in some people in some environments and not in others. It’s a rabbit-hole. In a few years, the correlation of a gene with a behavior might have the opposite connotation: it could imply that there is something you can do about it. “De-programming” is arduous and traumatic; someday, genetic surgery may seem the easiest, most painless course for changing behavior. Will future reactionaries hold people responsible precisely because they have a “gene for” homosexuality, obesity, criminality, promiscuity, or any of the other socially undesirable qualities eugenicists have been trying to genetically eliminate since the early 1900s?

Such is the cultural authority of science today that we believe a scientific justification to be irrefutable. But science, as John McPhee wrote, does not find the truth. Science erases what was formerly true. Every scientific theory ever proposed has been modified, qualified, or discarded. That alone should nullify it as the foundation of laws concerning moral issues. Genetic determinism can provide comfort to those who don’t want to blame themselves (or each other) for a trait, but it doesn’t stand the test. No, the more robust reason not to ban homosexuality is that it doesn’t fucking matter who someone falls in love with. Full stop.

Happy anniversary of the double helix, everyone. Solving the structure was a marvelous intellectual feat. But lawmakers and politicians, keep your hands out of my genes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.