BAM! A sharp thud on our little back deck about a yard from me the other day. I looked and saw a brick, lobbed over the fence by three kids in the alley. I yelled an obscenity and dashed for the gate. The kids took off and I gave chase, barefoot, indifferent to the shards of back-alley glass. The boys were young—between 9 and 12—brown-skinned. They outran me easily after a couple of blocks. But I got close enough to get a good look. They were clean and well-groomed. Nice-looking kids. They probably had moms who would give them a licking if they knew what their boys had done. Fortunately, no damage was done. I didn’t get a concussion or a bone bruise. It didn’t total my laptop. It didn’t shatter a window. The event was not serious in the wider scheme of city crime. But it was an invasion, a violation. It pissed me off and I thought about it the rest of the day. I weighed their crime as racially motivated. They were black and I am white and they probably wouldn’t have thrown that brick into a black family’s yard. Then I thought about it as motivated by class. Houses in our neighborhood are modest, but probably by those boys’ standards we are wealthy. I thought about how much violence lay behind the gesture. The beefy white cop who took my statement told me to dispose of the brick safely (lest it explode?) and suggested I work in a safer place than my back deck. The brick remains, as a reminder, and I continue to write in the garden. I will not be cowed by a nine-year-old. In the end, I concluded that class was more important than race—and mischief more important than class. The incident was the more troubling because two days earlier, I had also been writing outside when helicopters began circling. We live near a hospital with a Medevac, and traffic copters occasionally make a few passes when there’s a jam or an accident on a nearby artery, so a couple of minutes of their drone is normal. But these persisted, and then I saw that they were black police choppers. A few minutes later, a woman ran up our small one-way street screaming and wailing into her cell phone. We thought we heard her scream, “My baby!”

I checked the Baltimore PD Twitter feed and my heart sank:

Shooting. 3600 block Old York Road. Adult female and juvenile reported to be shot.

It was about five blocks from my house, across the busy thoroughfare marking my neighborhood from the friendly but sketchier one to the east. It’s not “The Wire” sketchy. Just a lower-middle-class neighborhood, mostly black, higher-than-average unemployment rate, lots of families and low-budget hipsters. Shootings are rare there, and broad-daylight gunplay is rare anywhere. But this particular afternoon, three-year-old MacKenzie Elliot was playing on the porch. Caught a stray bullet. Was dead by sundown. The piece I was trying to write that weekend was a review of several books, on genetic and cultural theories of race. One is Nicolas Wade’s A Troublesome Inheritance, which received a satirical review on these pages. It is a pernicious book, a defense of white privilege on biological grounds, cloaked in the same phony tone of reason that eugenicists and anti-evolutionists have evoked for decades: I just want to talk about this issue. Science has to be able to investigate any question, no matter how unpopular. Help help, the Political Correctness Police are trying to silence me. Blah blah blah.

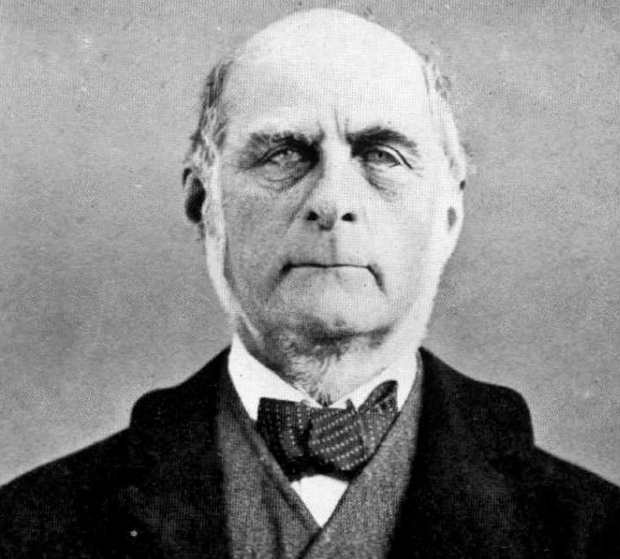

In the early 1980s, I learned that the nature/nurture controversy was officially over. The Victorian polymath Francis Galton had coined the phrase “nature vs. nurture” a century before.

Everyone knows now that it’s a false dichotomy. Everything interesting is shaped by both genes and environment, and moreover, genes and environment mold one another. The relative influence of genetics on a trait is not fixed; the trait may be primarily genetic under some conditions, primarily environmental under others. Scientists know this. Science journalists know it. Scholars of science know it. We have moved past it. Twenty-first century biology is about the interplay among heredity and environment: gene–gene, gene–environment, and environment-environment interactions.

Except it isn’t. Why else do we still have books like Wade’s? If anyone ought to be up on the latest findings in genetics it ought to be him, a long-time reporter on the genetics beat for the New York Times. Yet instead of providing a fair survey of the field as he was trained, he chose to be persuaded by a narrow slice of work that continues a long-discredited scientific tradition. One focusing on the biological race concept and its supposed connections with intelligence, sexuality and other tinderbox issues. As Sussman shows, much of this research is sponsored by the blatantly white-supremacist Pioneer Fund. When it comes to those qualities we think of as quintessentially human, the basic question of nature or nurture seems independent of the state of scientific knowledge. The question returns with force whenever the trait is morally charged. Sexuality. Violence. Intelligence. Race.

Since the 1970s, the brilliant Marxist population geneticist Richard Lewontin has been arguing that the essence of using genetics as a social weapon is equating “genetic” with “unchangeable.” For decades, Lewontin has been pointing out examples of how that’s not true. It’s even less true now, with biotechnology such as prenatal genetic diagnosis and genome editing. Increasingly, the eugenicists’ dream—the control of human evolution—seems to be coming within our grasp. The new eugenicists want to give individuals the opportunity to make the best baby money can buy. No government control, they insist, no problem: if the free market takes care of it, the ethical problems disappear. Adam Smith’s invisible hand will guide us toward the light. As we take control of our own children’s genomes, the rich white people may have rich white babies, but, once we equalize access to whole genome sequencing, IVF, and prenatal genetic diagnosis, then poor black couples can have,…um…the smartest little black babies they can. And so can the Hispanics! And the Catholics who believe procreation shouldn’t require intervention, well they can produce “love children,” just like in GATTACA. It’ll all be fair and market-driven, once we socialize it a little bit.

So why are we even still talking about race and IQ? To Wade and others who say that it is a reasonable scientific question, that proper science has no politics and that the Morality Police have no business blocking scientific progress, I respond: What progress? What benefit? In order to frame this as a scientific question one has to define race, and any definition of race has a moral dimension. There is no way to ask whether racial associations with IQ are “real” without an agenda. The association of race and IQ is a legitimate historical question, but it must be acknowledged that even the most objective historian can only be interested in that question for moral reasons. If the scholarship is good, the agenda will be transparent, evaluable, debatable. But not absent. A good scholar (or reporter) will seriously investigate other viewpoints, present all sides. But he or she will not make pretense to absolute objectivity. The great danger of scientific investigations of questions such as race and IQ is just that pretense.

Science has immense cultural authority—it is the dominant intellectual enterprise of our time. Consider the state of funding or education for “STEM” (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields versus that for the humanities, social sciences, or arts. A good deal of science’s cultural authority stems from its claims to objectivity. Thus when a scientist investigates race and IQ, or a science journalist writes about it, they can invoke a cultural myth of science as having privileged access to The Truth. Not all do it—those with historical sensitivity recognize and teach the fallibility of science. But it’s common enough, even among experienced science educators and reporters, to be a crucial justification for the scholarly study of science as a social process. Science has a potent Congressional lobby. Like any industry, it needs watchdogs. Science is not just any industry. Aspects of it remain curiosity-driven, independent of the profit motive. It has an aesthetic side that unites it with the arts. And yet, for many types of questions, it provides a pleasingly rigorous set of methods for cutting through bias and pre-expectation. When scientific methods are pitted against superstition, belief, and prejudice, I side with science every time.

But when you study a lot of science; when you examine it over broad swaths of geography and time, rather than focusing on one particular tiny corner of it; when you study the trajectories of science; when you study the impact of science; when you examine the relationship of science to other cultural enterprises; you find that scientific truth is always contextual. The science of any given day is always superseded by the science of tomorrow. Despite popular myth, science does not find absolute Truth. “Science erases what was formerly true,” wrote the author John McPhee. When I was in college, brain-cell formation stopped shortly after birth. The inheritance of acquired characteristics was debunked nonsense. Genes were fixed and static. Humans had about 100,000 of them. IQ did not change over one’s lifetime. There were nine planets in our solar system. All of that was scientifically proven. None of it is true any more. Only a scientist ignorant of history can be confident that what she knows now will still be true a generation hence.

Which brings me back to the murder and the brick. On one level, the shootings a few blocks away were another incident of violence, probably drug-related, in a poor, predominantly black neighborhood. When they catch the bastard that shot that little girl, if they do a DNA test they might find genetic variants that occur with higher frequency in black males than in the population as a whole. If I catch the little punk who nearly beaned me with that brick, should he spit on my clothes and were I to have it analyzed, the lab might find SNPs in his DNA associated with a predisposition to violence. Whether those differences exist are legitimate scientific questions. But they are moot. The only reason to ask them is to prove an innate predisposition that, historically, has tended to foster racism and hinder social change. They may be legitimate scientific questions, but they’re stupid questions, and the motives of anyone who asks them are suspect. It’s not censorship to declare certain inquiries out-of-bounds. And people knowledgeable about science but outside the elite ought to be part of the process. Scholars. Journalists. Technicians. Students. Research funding should be less of a plutocracy, more of a representative democracy, so we can make better decisions about what questions are worth asking. In my case, the right questions are not “What biological differences account for that brick or that murder?” They are, Who is that brick-throwing kid’s mom? Can I, a “rich” white male, win her trust enough for her to let me into her house, to tell her my story in a way she can hear, so that she can discipline her child and get him back on a more positive path? What can we do to take our neighborhoods back, to make them not shooting galleries but communities again? How can we get people to get to know their neighbors, to keep their eyes open, to watch out for each other?

The other night, my wife took me along to an impromptu wake for the murdered girl, a five-minute bike ride away, near where the shootings occurred. In conventional racial terms, the crowd looked like Baltimore: about two-thirds black, one-third white (the latter mostly young), a sprinkling of Asians. But culturally, it was a black event, run by black women. The MC was the head of the neighborhood community association, a black woman. Words were said by the mayor, a state senator, a city councilwoman—all black women—and the governor, a white man. There was a prayer led by Sister Tina, a holy-rolling preacher who could make a middle-aged, over-educated, white atheist’s eyes well with her furious message of love and community. After the prayers and speeches, one young man threw down a Michael Jackson imitation, lip-synching and doing every move in Michael’s bag—full splits, knee-drops, and skids—on the coarse, hot Baltimore asphalt. The crowd whooped its approval. But the power that evening was held by the women. As we got ready to leave, I walked up and introduced myself to a few of those formidable, warm women. I threw my arms around Sister Tina and told her I thought she was amazing. She beamed and said she could see that the light of God was in me, she could see that I understood. And maybe I did. I know too much about evolution to believe in a literal god, but our mutual warmth and shared ideals are real. It may have been a culturally black event, but all were welcome. I understood in a new way how race matters in exactly the ways, to precisely the extent, that we want it to. Searching for the SNPs that make “them” and “us” different, seeking differences in test scores between the mixture of genes and culture Americans call “black” with those we call “white,” divides us. But here in this corner of this city, we have opportunities to celebrate each other’s cultures, and we have opportunities to share each other’s grief. The more I take those opportunities, the less value I see in the sciences of human racial difference.

It really is a bloody shame that India just had yet another free and fair election, because Nicholas Wade’s new book is so bally good it makes me want to dig out the old pith helmet and mustache wax and jolly well troop off and colonize her again. Since I can’t conquer India, I itch to conquer Mrs. Dorkins and spread my genes, via more little Dorkinses. Alas, Wendy says she has a headache (again!), so the next best thing is to dab my favorite plume into grandfather Dorkins’s inkpot and, in my best public-school hand, pen this little squib on behalf of Wade’s latest. Perhaps I can prompt the some of you lot to do your Darwinian duty and either have or not have more children, depending on your race.

It really is a bloody shame that India just had yet another free and fair election, because Nicholas Wade’s new book is so bally good it makes me want to dig out the old pith helmet and mustache wax and jolly well troop off and colonize her again. Since I can’t conquer India, I itch to conquer Mrs. Dorkins and spread my genes, via more little Dorkinses. Alas, Wendy says she has a headache (again!), so the next best thing is to dab my favorite plume into grandfather Dorkins’s inkpot and, in my best public-school hand, pen this little squib on behalf of Wade’s latest. Perhaps I can prompt the some of you lot to do your Darwinian duty and either have or not have more children, depending on your race.

My review

My review A diet rich in DNA—and its molecular cousin, RNA—is correlated with improved performance across a wide range of activities, both physical and mental, and could help stave off the effects of aging. Results of a bold new study from Kashkow University’s School of DNA and Medicine, expected to begin next year, were announced yesterday. They have been called a “breakthrough” and a “game-changer” by some of the leading scientists on the proposed study.

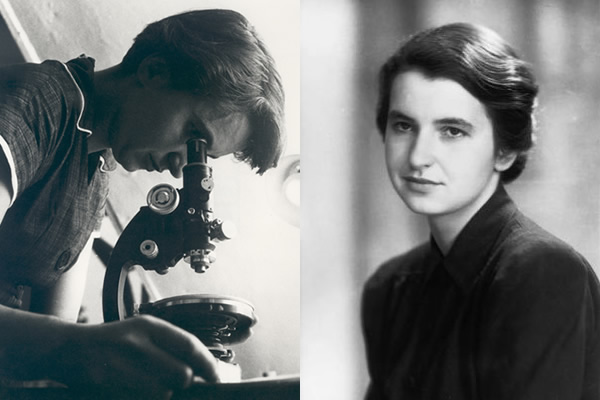

A diet rich in DNA—and its molecular cousin, RNA—is correlated with improved performance across a wide range of activities, both physical and mental, and could help stave off the effects of aging. Results of a bold new study from Kashkow University’s School of DNA and Medicine, expected to begin next year, were announced yesterday. They have been called a “breakthrough” and a “game-changer” by some of the leading scientists on the proposed study. Athletes, too, are recognizing the benefits of upping their intake of what double helix co-discoverer Francis Crick called the “secret of life.” DNA is being mixed with branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—some of the building blocks of protein—to create potent muscle-building supplements. An Australian company offers a patented “

Athletes, too, are recognizing the benefits of upping their intake of what double helix co-discoverer Francis Crick called the “secret of life.” DNA is being mixed with branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—some of the building blocks of protein—to create potent muscle-building supplements. An Australian company offers a patented “

Animal rights’ groups, however, have protested the freeze-drying of lambs. A spokesorganism for PETNA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Nucleic Acids) notes that even in a wool coat, the young ovines must get the shivers during the process.

Animal rights’ groups, however, have protested the freeze-drying of lambs. A spokesorganism for PETNA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Nucleic Acids) notes that even in a wool coat, the young ovines must get the shivers during the process. Nevertheless, not everyone is convinced of the value of megadoses of DNA. Dr. Ron Swanson, of the University of California at Boulder, believes that prokaryotic nucleic acid is at best worthless and perhaps damaging. “The highest quality DNA comes from steak and cigars,” he says. Further, he continues, it is not the quantity but the “balance” between DNA and RNA that provides the key to health. “Our studies show that RNA/DNA imbalance is the root cause of a variety of symptoms,” he said. “If you feel fatigue, weakness, muscle and joint stiffness, memory loss, or lack of ability to concentrate, restoring the correct balance has been shown absolutely equivocally to sometimes help stuff,” he said.

Nevertheless, not everyone is convinced of the value of megadoses of DNA. Dr. Ron Swanson, of the University of California at Boulder, believes that prokaryotic nucleic acid is at best worthless and perhaps damaging. “The highest quality DNA comes from steak and cigars,” he says. Further, he continues, it is not the quantity but the “balance” between DNA and RNA that provides the key to health. “Our studies show that RNA/DNA imbalance is the root cause of a variety of symptoms,” he said. “If you feel fatigue, weakness, muscle and joint stiffness, memory loss, or lack of ability to concentrate, restoring the correct balance has been shown absolutely equivocally to sometimes help stuff,” he said.

Should we be concerned? Absolutely. Should we condemn the procedure? Not unless we wish to be hypocrites. It is on one level a preventive medical treatment like any other and banning it would deny certain people—admittedly, all of them wealthy enough to shell out tens of thousands of dollars to get pregnant—access to available healthcare. But yes, it certainly is a slippery slope. There simply is no defensible way to draw a hard, bright line between medicine and eugenics. It provides a spectrum, from preventing disease to maximizing health to genetic enhancement. This ambiguity is in the nature of genetic medicine. We are heading down this path and simply digging in our heels will not be productive.

Should we be concerned? Absolutely. Should we condemn the procedure? Not unless we wish to be hypocrites. It is on one level a preventive medical treatment like any other and banning it would deny certain people—admittedly, all of them wealthy enough to shell out tens of thousands of dollars to get pregnant—access to available healthcare. But yes, it certainly is a slippery slope. There simply is no defensible way to draw a hard, bright line between medicine and eugenics. It provides a spectrum, from preventing disease to maximizing health to genetic enhancement. This ambiguity is in the nature of genetic medicine. We are heading down this path and simply digging in our heels will not be productive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.