A flurry of eugenics-related news over the last couple of weeks demonstrates that we have to stop considering eugenics a historical period and think about it more as an ever-present theme. In my book I called it “the eugenic impulse”—not to invoke some sort of misty, mystical force but rather simply to point to something that seems deeply part of our nature. Which is not to say part of our DNA. My research convinced me of two things:

1) Mixed with the chauvinism, intolerance, and paternalistic governmentality of Progressive-era eugenics was an impulse to prevent disease and disability using state-of-the-art knowledge of heredity.

2) Mixed with present-day impulses to prevent disease and disability using state-of-the-art knowledge of heredity is a great deal of hype motivated more by the desire for profits than by humanitarian concerns.

In short, I could not escape the conclusion that some aspects of contemporary genetic medicine—both good and bad—are indistinguishable from some aspects of Progressive-era eugenics—both good and bad.

The Science of Human Perfection is my attempt to wrestle with the question, “Is eugenics ever okay?” Because I have refused to come down on the side of the dogmatic anti-eugenicists, some pro-eugenics types, eager for recruits, have marshaled my words for their cause. At the same time, some antis have accused me of supporting the enemy. If I make the argument that modern medical genetics comes from the same rootstock as Progressive-era eugenics, they fear that anti-abortion fanatics will use my work as ammunition to repeal Roe v. Wade.

To those of you on both extremes, here’s my answer: No, eugenics is not okay. It scares the crap out of me, to be honest. But it’s happening anyway. No one—and certainly not a historian—is going to stop us from using genetic technology in the attempt to perfect the human race. The most intelligent response is to point out (and so hopefully avoid) the greatest risks.

*

For years, historians of eugenics have maintained that the term eugenics is no longer helpful. It is too loaded, they say; invariably, it invokes the Nazi past. Whatever programs in controlled breeding or self-directed evolution may be going on, it’s alarmist and a distraction, they say, to call them “eugenics.” For years, this was a reasonable and level-headed response, but it is no longer viable. Not because it’s less loaded, but because today’s historical actors are using it.

A growing number commentators from within the scientific community are arguing for a revisitation of eugenics:

“Seeing the bright side of being handicapped is like praising the virtues of extreme poverty. To be sure, there are many individuals who rise out of its inherently degrading states. But we perhaps most realistically should see it as the major origin of asocial behavior that has among its bad consequences the breeding of criminal violence.” (James Watson, “Genes and Politics,” 1997)

“We are once again practicing a sort of eugenics” (Matt Ridley, “The New Eugenics,” 2000)

In 2001, the conservative theorist Richard Lynn published Eugenics: A Reassessment, which argues just what you think it does. In 2002, researcher DJ Galton (no relation to the founder of eugenics) considered the new genetics, test-tube babies, and genetic screening and called a spade a spade: Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century.

“Eugenics failed because it was not scientific enough…The role of eugenics in our time is in maximizing [hereditary] information and its availability to those who need it and minimizing the temptation to use the State as the means of enforcing eugenic ideals.” (Elof Carlson, “The Eugenic World of Charles Benedict Davenport,” 2008)

“A new interest in rational discourse about eugenics…should be our goal.” (Maynard Olson, “Davenport’s Dream,” 2008)

“Soon it will be a sin of parents to have a child that carries the heavy burden of genetic disease. We are entering a world where we have to consider the quality of our children.” (Bob Edwards [creator of first test-tube baby])

“Eugenics, once discredited as part of the first wave of social authoritarian progressives that trampled free will for women, handicapped people and minorities, is attempting a 21st century comeback.” (Hank Campbell, “Genetic Literacy Project on Neo-Eugenics,” 2012)

“To a great extent we already live in the second age of eugenics.” (Razib Khan, “Eugenics, the 100 year cycle”, 2012)

The most recent is Jon Entine, who runs the Center for Genetic Literacy and writes regularly for the conservative money magazine Forbes. “Instead of being driven by a desire to ‘improve’ the species,” he writes, the “new eugenics is driven by our personal desire to be as healthy, intelligent and fit as possible—and for the opportunity of our children to be so as well.” (Jon Entine, “DNA Screening is Part of the New Eugenics—and That’s Okay,” 2013)

No, we are not trying to improve the species—just our children, and our children’s children, and our children’s children’s children,…

Talk of a new eugenics, then, is no longer idle hand-wringing. When our actors themselves are using the term, historians and philosophers need to take notice and help make sense of it.

*

The fact that Entine writes for Forbes, Ridley for the National Review, and Lynn for Mankind Quarterly suggests a linkage between the new eugenics and conservative ideologies. Eugenics has long had such associations. Some of the neo-eugenicists (e.g. Lynn) are ideologically linked to the old, discredited eugenic ideologies. But others (e.g., Ridley, Entine) I think are more complicated. Liberals and conservatives, of course, are a diverse lot. When critiquing neo-eugenics, we must bear in mind whether someone is writing from a position of profit-making, preservation of the social status quo, libertarian individualism, or other ideology.

Further, liberals can be eugenicists too. As Diane Paul showed years ago in “Eugenics and the Left,” political liberals were also deeply involved in eugenic schemes during the Progressive era. Most historians of eugenics agree that to a first approximation, everyone in the Progressive era was a conservative. Sterilization legislation was democratically approved, and most sterilizations were carried out in state hospitals, under at least a premise of social benefit. There may well have been a conservative slant to Progressive eugenics, but it was only a slant, and by the 1930s eugenics probably had a liberal slant.

Because of this political ecumenicalism, eugenics today makes for some strange political bedfellows. If some pro-eugenics advocates lean conservative, so do some antis. The Catholic Church—hardly a bastion of liberal fanaticism—opposes eugenics on grounds that it generally entails either abortion or embryo selection. Matt Ridley favors eugenics and is a pro-business conservative. Genetic screening can be seen as a liberal, feminist issue—an issue of women’s choice and empowerment. Or it can be seen as a tool of government social control. Finally, genetic screening and eugenics are not necessarily the same thing. The Center for Genetics and Society supports abortion and genetic screening but seeks to establish a critical biopolitics that can help shape policy to reap the benefits and avoid the risks of reproductive technologies—a position Entine constantly takes them to task over, presumably because they are not simple cheerleaders.

Eugenics, then, does not hew unswervingly toward either pole of the political spectrum. The eugenics question forces us to parse some traditionally liberal and conservative ideas in new ways. Favoring genetic technology is pro-business (conservative). Favoring prenatal genetic diagnosis with abortion is pro-choice (liberal). Fearing the power of genetic manipulation falling into the hands of totalitarian regimes: liberal. Favoring open markets and “consumer choice”: pro-business conservative. Sometimes this consumer-driven eugenics is even called “liberal eugenics.” Perhaps that’s a smokescreen, but maybe not entirely.

Political ideology, then, can’t help us make an easy decision on whether eugenics is ever okay. If the new eugenics has a conservative tilt it’s only a tilt, and there’s plenty of counterweight on the other side. Unfortunately, we’re going to have to make up our own minds.

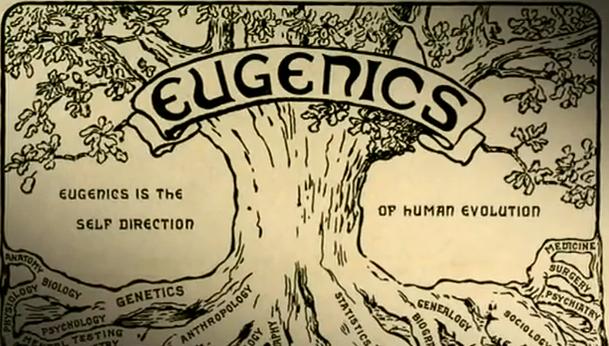

To do that, we first have to accept that the eugenic train has left the station. Understood as “the self-direction of human evolution” (the slogan from the 1921 eugenics congress and for me still the most inclusive definition I’ve found), eugenics is going to happen. Is happening. Always happens. For now, it’s still mainly for elites who can afford expensive IVF and genetic screening, but the cost of those procedures is dropping rapidly and more people are gaining access to it each year. Many people are in fact currently making eugenic choices, from the wealthy who can afford prenatal genetic diagnosis with selective abortion to the Dor Yeshorim who screen for and discourage marriage between carriers of Tay-Sachs and a range of other genetic diseases. On this much, I agree with folks like Entine. Where we part company is that I’m not nearly so sanguine about it as he seems to be.

Recognizing that we are grasping the reins of human evolution as fast as we can raises two sets of concerns. First, “What if it doesn’t work?” It’s been argued for some time that our technological capacity greatly outstrips both our wisdom and our understanding. It’s often argued that genetic choices have been made since the dawn of marriage, so opposition to techniques such as embryo selection is mere technophobia. But even age-old holistic breeding practices have unpredictable, undesired effects. Sweet-tempered Laborador retrievers tend to get hip dysplasia and eye problems. Great Danes’ hearts fail. Some quarter horses are prone to connective tissue disorders or “tying up” episodes related to their highly bred musculature. The European royal families are prone to hemophilia and polydactyly. Selecting for single genes, rather than traits that involve suites of genes that have evolved together, seems likely to exacerbate such unintended consequences. The emerging science of systems biology holds that genes act—and hence evolve—in networks. Selecting for particular genes rather than complex traits disrupts those networks and is likely to have unpredictable effects.

We in fact have very little idea how the genome works. The genome is like an ecosystem, a brain, or the immune system: an immensely complex, deeply interconnected system. Altering one element or a few elements has effects that are not only unknown but in many cases unpredictable. Evolution, Darwin showed, is an immensely slow process, in which innumerable parts “negotiate” with one another to produce the best-adapted organisms in a given environment at a given time. In taking control over that process, we will be altering the “ecology” of the genome, and it’s bound to have similar effects to our impact on the environment. With great wisdom, it might be handled safely, but experience does not give one much hope for collective human wisdom.

The second concern is, “What if it does work?” What if it does indeed become possible to select traits—health, height, complexion, intelligence—without creating cruel monsters? I have enough faith in technology that I think this may eventually happen. Some unforeseen consequences will doubtless occur, but in time they will become correctable. So what do we do when this becomes possible? We need to keep in mind that this will be a tool of the upper strata of society for a good long time. The rich will do it more than the poor, and Americans and Europeans will do it more than Bangladeshis and Somalians. So it will be a way of inscribing socioeconomic status literally in our DNA. This is in fact a conservative application, because it will tend to reinforce the socioeconomic status quo.

Further, in most developed countries, it’s not government control we need to worry about; it’s corporate control and the tyranny of the marketplace. Advertisers will push certain genotypes. Ad campaigns, current styles, and the rapidly shifting current consensus on what is or is not healthy will shape people’s genetic decisions. And of course, you can’t shed your genome the way you can last year’s fashions. The concern here, then, is that the new eugenics harnesses long-term processes in the service of short-term goals. This too will have unpredictable effects. History shows without a doubt that societies are rarely wise; we have great trouble seeing several moves ahead, planning for the future, delaying gratification, or sacrificing some of next quarter’s earnings so that we may reap greater health and happiness some time in the future. Even more troubling than failures of technology, then, are failures of morality. And glib reassurances that we are beyond Nazi-style totalitarianism do little to comfort me. The age of self-interested individualism can be just as scary as that of communal self-sacrifice.

Most critical analyses of past eugenic efforts have centered on race, class, and gender. I think that the greatest concern with the new eugenics will likely be the fourth member of the “big three”: disability. Another recent story concerns the stunning development of a method of “silencing” chromosomes. Every nucleated cell in a woman’s body uses this to turn off one of her two X chromosomes; otherwise, women would have a double dose of X chromosome genes, which would lead to lots of problems. The advance is in harnessing this technique so that it can be applied to non-sex chromosomes. Down syndrome results from an extra (third) chromosome 21. The blogs and papers have been awash lately with speculations about “shutting off” the extra chromosome 21 in embryos, to prevent Down syndrome.

The problem is that the severity of Down’s is unpredictable. A family might well be happy to have a high-functioning Down’s baby, but a severely affected child suffers greatly, as does its parents. Who would take that chance? If (when) this technique becomes widely medically available, the frequency of Down syndrome will drop, simultaneously reducing suffering among the victims and families of severe Down’s and joy and love among those close to high-functioning Down’s patients. No humane person would never wish, say, Down syndrome on a family not equipped to handle such a child. But nor would I want to live in a society lacking in people with Down syndrome, or little people, or the blind. It’s not a wish for suffering; we all suffer. But engineering our own evolution will likely have a normalizing effect. Intolerance of abnormality was, indeed, a common refrain among Progressive-era eugenicists and greater power over our genetic future is only likely to increase it. The movie GATTACA got this much right: genetic disease leads to suffering—but so does intolerance.

Is eugenics ever okay? On the individual scale, of choosing not to raise a child with a debilitating disease, I think we have no moral choice but to condone it. A prospective parent talking with a genetic counselor about whether to prevent a deformed or diseased baby from being born is in fact a form of eugenics. But my research made it irrefutable that eugenics has always been simultaneously about individuals and populations. Individual choices lead to population changes—and individual choices are influenced by more than objective genetic knowledge. Although those parents’ choice is for their family rather than the race, they are simultaneously participating in the self-direction of human evolution—it is a choice that any Progressive-era eugenicist would have condoned. And, granting the right to abortion and embryo selection, that is an entirely moral choice.

But what influences that parent’s choice? The biomedical industry hides truly fantastic profits behind the cloak of “health.” Moving responsibly into this inevitable future demands that someone call out the self-interest of the diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies, the instrument-makers and laboratories, the hospitals, the advertisers, and the investors in this new age gold mine. It demands analysis of subtle forms of coercion. It demands a jaundiced eye. Skepticism isn’t Luddism, isn’t anti-choice, isn’t anti-health. It’s following the money.

Much as one might wish to do so, the genie can’t be stuffed back into the bottle. The new eugenics is here. This worries me greatly. But worry, by itself, solves nothing. The concerns it raises are too complex for either dogmatism or complacency. It comes with new, subtle kinds of coercion. Science alone cannot be our guide into this brave genetic world. The closer we come to guiding our own evolution, the more important a humanistic perspective—one that takes the long view of history and the broad view of social context—becomes in helping us make sense of it. The future is here, and, dammit, it’s complicated.

[Update 7/26/13 3:20 pm: Changed description of the Center for Genetics and Society to more accurately reflect their philosophy and agenda. H/t Alex Stern.]

Hi Nathaniel:

Thanks for helping us to bushwhack through the ethical and historical thicket of the viability, acceptability, and potential consequences of 21st century eugenics.

I’ve tended to think of as two intertwined currents: the first Eugenics with a capital “E” that reigned from the 1910s to the 1960s. During this period there were eugenics organizations, laws, and publications, that helped to shore up policies that excluded and policed based on racial identity/classification, disability, perceived immorality or deviance, and eugenics. Embedded in this current and continuous to this day was eugenics with a lower-case “e” which I think is analogous to your “eugenic impulse.” The great irony of course is that when Eugenics existed the tools were clunky (i.e. sterilization, really?, to bred out traits on a population level) but today the tools, like silencing chromosomes or prenatal non-invasive screening, have much greater precision. Thus I see many technologies being rolled out today that have visible and less visible eugenic overtones, implications, and potential outcomes (the high termination rate of fetuses with trisomy 21 being most obvious example). At the same time, violations like sterilization abuse with strong eugenic overtones (i.e., recent revelations about 150 unauthorized operations in California women’s prisons) continue in the United States and other parts of the world.

On one hand, it’s good that the usage and availability of genetic technologies and tests are not controlled by state programs or governmental entities; on the other, it’s very worrisome to see the rapid commercialization of tests and technologies that are marketed and sold in the name of “healthy babies” and “health enhancement” without much questioning about their inherent values about human worth, differently abled bodies, and the virtues of human variation. I’ve thought about this question in terms of the important role of genetic counselors in the 1970s, when they, mainly women, redefined the field and incorporated bioethical and psycho-social issues into how genetic information was conveyed and they thought in complex ways about risk, stigma, and the prevention model. Then the concern appropriately was more about state coercion, harkening back to the dark days of eugenic sterilization and in Germany mass euthanasia. But as you point out, today that critical perspective needs to be applied to what Rob Resta has called Big Genoma. Conflict of Interest is an important topic, as is a steady critique of the extant and potential problems associated with DTC testing, which is growing rapidly.

The point is not that companies should not develop genetic technologies and tests, and women should be able to use these tools as part of reproductive decision making — there is great value and promise in clinical genetics. But, and here I think we have a real deficit of this in the United States, we need to evaluate the values embedded in these tests. Thus, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics was very careful in its recent position statement on NIPS to clarify that this “test” is screening not diagnostic, that it is not ready for “first tier” use, and, very importantly, to include a least a short bit of neutral to positive information about Down Syndrome. Many genetic counselors and geneticists feel this kind of education is necessary and should be greatly expanded, as should knowledge of the limitations of something like NIPS, whose over 90% numbers of specificity and sensitivity are not nearly as certain as they appear to be (see Katie Stoll’s recent post on the DNA Exchange).

So before it was easy as a historian to study Eugenics; today it’s much more challenging to critically examine, and often even satisfactorily define the parameters of, eugenics.

Beautifully put. I agree whole-heartedly. Raymond Pearl used to make the same distinction. He was horrified by “capital-E” eugenics (the movement) but always remained in sympathy with “small-e” eugenics, the impulse to use genetic information to relieve suffering and improve society.

And I agree also that we need to evaluate the values embedded in genetic screening, diagnostics, gene therapy, and so forth and so on. They all have different valences and they need to be distinguished. And also, I’d go so far as to say that although genetic counseling, bioethics, science policy, and so forth can all be incredibly helpful tools, in the end, we are going to have to make our own decisions about these things. That is a frightening prospect, frankly, but one we seem to have little choice but to face. In my clumsy and personal way, I am trying to take a step toward that–to provide at least a model of how one person is trying to wrestle both compassionately and reasonably intelligently with this eel-barrel of issues.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments!

Can you discuss Savelescu’s Procreative Beneficence in the context of these new genetic screening technologies? (Screening that then often triggers definitive diagnostic testing)

It seems normal for parents to desire healthy offspring. Is it evil or morally suspect for a couple to choose healthy offspring?

Great question! I gave it a separate post. Hope this at least begins to answer some of your concerns.

But nor would I want to live in a society lacking in people with Down syndrome, or little people, or the blind.

Why would you not want to live in this society? Would want to have one of these conditions for yourself or a family member?

But nor would I want to live in a society lacking in people with Down syndrome, or little people, or the blind.

Why would you not want to live in this society? Would you want to have one of these conditions for yourself or a family member?

A former student of mine has a sibling with Down syndrome. She loves him deeply and wouldn’t trade him for anyone else. Down’s patients love uniquely, and those who love them do as well. Having a Down’s brother, being involved in the Down’s community, has made this woman tough, kind, mature, and a superb leader. I hope that if I had a Down’s sibling, for example, I would show the compassion and strength of character that her experience has developed in her. Her brother, the Down’s patient, has thus made the world a better place and has harmed no one. Who are you–or who am I–to decide he shouldn’t exist?

Have a look at the resources at the Medicine After the Holocaust website http://www.medicineaftertheholocaust.org/

If the Germans had not invaded other countries but only killed their own citizens I doubt the rest of the world would have cared enough to forcibly stop it.

While eugenics did lead to sterilization and killing of disabled people it was not the cause of the Holocaust. The cause of the Holocaust was religious and not medical, see http://ffrf.org/legacy/fttoday/1997/march97/holocaust.html

The particular religious cause of the Holocaust was the Bible and Christianity. See the book Why the Holocaust Happened : Its Religious Cause & Scholarly Cover-Up [Paperback] Eric Zuesse (Author) and site http://hwarmstrong.com/why-the-holacaust.htm

I don’t think your response hits the point. We can respect and care for every human without giving a positive choice to suffering and disability. Our everyday lives are all about reproductive choices. Entire chunks of culture are devoted to mate selection.

She loves him because he is her brother, not just because he has Down syndrome. And those with Down syndrome are not all happy, see http://www.research.leiden.edu/news/stereotype-of-children-with-down-syndrome.html

His parents have the right to decide, or left the decision to chance.

If you had to choose between two embryos to implant, one with Down syndrome or one without, which would you choose for your child? Do you wish that you had been born with Down syndrome?

And not everyone without Down syndrome is happy either.

While we need not be Pollyannish about the challenges of living with intellectual or physical disabilities, nor should we assume that “normal” is also the most desirable or even most superior, biologically or otherwise.

The real rub is how to balance reproductive autonomy and medical benefits of genetic and reproductive technologies with values that also support disability rights. Unfortunately, this is one of those ethical areas where two acceptable options or perspectives might both be right, which, in turn, suggests that moral relativism (i.e., decisions about pregnancy based on individual circumstances) is the most likely destination.

In some instances all of these currents are under attack, for example, in North Dakota, which recently passed a law banning abortions for genetic defects (primarily targeting trisomy 21). This is being contested in the courts, but it manages to restrict reproductive autonomy and discourage use of reproductive and genetic technologies, while failing to promote or embrace a positive understanding of people with disabilities.

Beautifully put, Alex! Agree completely–it’s precisely that conundrum I tried to convey in the piece.

I’m going to ignore Jeffrey’s idiotic comment about the Germans and assert that we all basically agree here: the parents must have the right to decide, and should not be castigated for either choice: to have or not to have a baby with a given disability.

The right context for such decisions seems to be at the level of the individual and family. Grand visions of population and evolution mostly misguided.

But … at the level of public health and health care systems it still might be useful to account for the suffering and pain and economic costs of genetic disorders. While respecting individuals we can still note that about 8% of health care costs in Europe are devoted to individuals with developmental disabilities.

I think that parents who choose not to use prenatal testing and selective termination of disabled fetuses should be castigated. Now that the technology is available it should be used. For the same reason that we should castigate parents who do not vaccinate their children or prosecute parents who refuse them medical care.

http://www.uic.edu/depts/mcam/ethics/refusal.htm

These are issues where it is really important to respect individual privacy. There is no place for castigation. There is no avoiding suffering whether you are ‘normal’ or not. Look at genome sequencing data and what you see is the potential for disease and disability in 100% of us (not to mention actuarial data). The question of when we will suffer is the only thing on the table.

I think Eugenics is never ok. Some things you just don´t touch. Stop eugenics!

You are so cool! I don’t think I have read through a single thing

like this before. So great to find someone with original thoughts on this topic.

Really.. thanks for starting this up. This site is something that’s needed on the web, someone with a little originality!