Yesterday I and seemingly everyone else interested in genomes posted about the FDA letter ordering the genome diagnostics company 23andMe to stop marketing their saliva test. FDA treats the test as a “medical device, because “it is intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or is intended to affect the structure or function of the body.” The company first issued a bland, terse statement acknowledging the letter and then company president Anne Wojcicki signed a short post affirming the company’s commitment to providing reliable data, promising cooperation with FDA, and reasserting her faith that “genetic information can lead to better decisions and healthier lives.” (I say she “signed” it because of course we have no way of knowing whether she composed it and she’s no fool: surely the text was vetted by Legal.) In other words, the company followed up with a bland, less-terse response, carefully worded to reassure customers of the company’s ethical stance and core mission. Reactions to the FDA letter range from critics of the company singing “Hallelujah!” to defenders and happy customers are attacking FDA for denying the public the right to their own data. The 23andMe blog is abuzz and, hearteningly, a few sane souls there are trying to dispel misinformation.

I am doing history on the fly here. If journalism is the first draft of history, let’s take a moment to revise that first draft—to use the historian’s tools to clear up misconceptions and set the debate in context as best we can. The history of the present carries its own risks. My and other historians’ views on this will undoubtedly evolve, but I think it’s worth injecting historical perspective into debates such as these as soon as possible.

*

We must be clear that the FDA letter does not prohibit 23andMe from selling their test. It demands they stop marketing it. The difference may not amount to much in practice—how much can you sell if you don’t market your product?—but the distinction does help clarify what is actually at stake here. FDA is not attempting to instigate a referendum on the public’s access to their own DNA information. They are challenging the promises 23andMe seems to make. This is, in short, not a dispute about access, but about hype.

The company seems to promise self-knowledge. The ad copy for 23andMe promises to tell you what your genome “says about you.” “The more you know about your DNA,” they trumpet, “the more you know about yourself.” On one level, that’s perfectly, trivially true: your genome does have a lot to do with your metabolism, body structure, how you respond to disease agents, and so forth. The problem is, we as yet know very little about how it all works. The 23andMe marketing exploits a crucial slippage in the concept of “knowledge,” which FDA correctly finds misleading. In short, the marketing implies a colloquial notion of knowledge as a fixed and true fact, while the science behind the test is anything but.

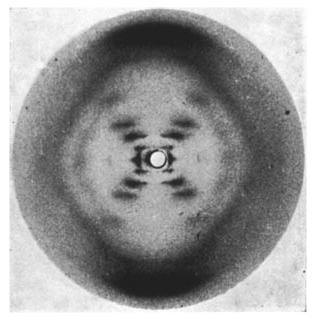

Historians and other scholars of science have thought a lot about the concept of scientific knowledge. In 1934, Ludwik Fleck wrote about the “genesis and development of a scientific fact,” namely the Wasserman test for syphilis. It is a pioneering classic in a now-huge (and still growing) literature on how scientific facts are created. Science claims to gather facts about nature and integrate them into explanations of natural mechanisms. A moment’s reflection reveals that very few scientific facts last forever. Most, perhaps all, undergo revision and many are discarded, overthrown, or reversed. They are historical things, not universal truths. A surprisingly small amount of what I learned in science courses 20 and 30 years ago is still true. As that great philosopher of science John McPhee wrote, “science erases what was previously true” (Oranges, p. 75). Because scientists search for universal, timeless mechanisms, they easily slip into language suggesting that they discover universal, timeless truth. But there is uncertainty, contingency, malleability built into every scientific fact.

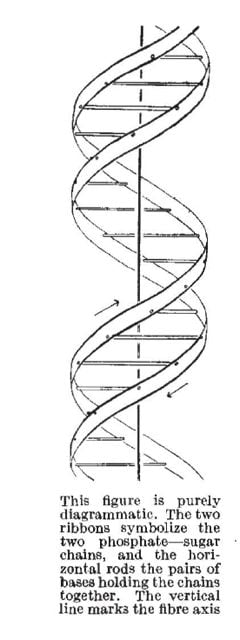

This goes double for genome information. The 23andMe product, like every genome test, provides probabilities of risk, not mechanisms. Probabilities are messy and hard to understand. They carry an almost irresistible tendency to be converted into hard facts. If you flip a coin 9 times and it comes up heads every time, you expect the next flip to come up tails. And if you get heads 49 times in a row, the next one has got to be tails, right? Even if you know intellectually that the odds are still 50:50, just like on every previous flip. You can know you have a particular gene variant, but in most cases, neither you nor anyone else knows exactly what that means. Despite the language of probability that dots the 23andMe literature, their overall message—and the one clearly picked up by many of their clientele—is one of knowledge in the colloquial sense. And that is oversell.

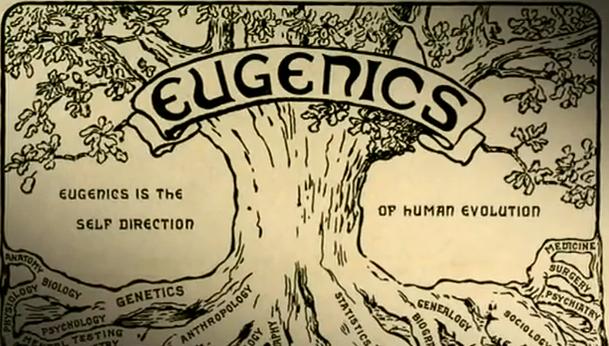

Human genetics has always been characterized by overstatement and hype. In the early 1900s, the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws persuaded many that they now understood how heredity works. Although every scientist acknowledged there was still much to learn, prominent students of human heredity believed they knew enough to begin eliminating human defects through marriage and sterilization laws. We now view such eugenic legislation as almost unbelievably naive. Combine that naivete with race, gender, and class prejudice and you obtain a tragically cruel and oppressive eugenics movement that resulted in the coerced sterilization of many thousands, in the US and abroad—including, of course, the Nazi sterilization law of 1933, based on the American “model sterilization law,” which culminated not only in racist forced sterilization but euthanasia.

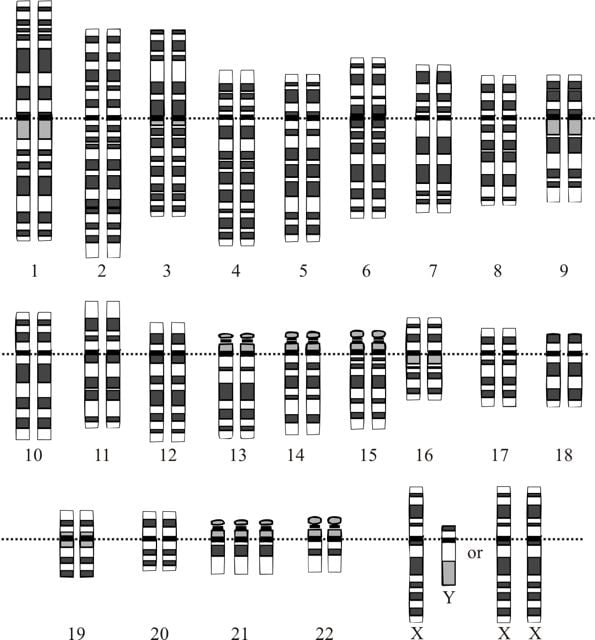

Human-genetic hype hardly ended with the eugenics movement. In 1960s, as human diseases were finally being mapped to chromosomes, it seemed transparent that if a chromosomal error that produces an individual with an XXY constitution feminizes that individual (which it does), then an extra Y chromosome (XYY) must masculinize. Such “super-males,” data seemed to suggest, were not only taller and hairier than average, but also more aggressive and violent. It was, for a while, a fact that XYY males were prone to violent crime.

The molecular revolution in genetics produced even more hype. When recombinant DNA and gene cloning techniques made it possible to try replacing or augmenting disease genes with healthy ones, DNA cowboys hyped gene therapy far beyond existing knowledge, promising the end of genetic disease. The 1995 Orkin-Motulsky report acknowledged the promise of gene therapy but noted,

Overselling of the results of laboratory and clinical studies by investigators and their sponsors…has led to the mistaken and widespread perception that gene therapy is further developed and more successful than it actually is.[1]

Soon after this report was published, Jesse Gelsinger died unexpectedly in a gene-therapy trial, patients in a French gene-therapy trial for adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency unexpectedly developed leukemia, and the gene-therapy pioneer W. French Anderson was arrested, tried, and convicted on charges of child molesting—in other words, abusing and overestimating his power over the children whose health was entrusted to him. The risks of failing to heed warnings about genetic oversell are high.

*

Like gene therapy, genome profiling has great promise, but the FDA letter to 23andMe is a stern reprimand to an industry that, like gene therapy and the entire history of human genetics, blurs the line between promise and genuine results.

The current controversy over commercial genome profiling has two qualities that distinguish it as particularly serious. First, unlike previous examples of overselling human genetics, it is profit-driven. The “oversell” is more literal than it has ever been. Although 23andMe presents as a concerned company dedicated to the health of their clientele, they are also—and arguably primarily—dedicated to their stockholders. In a for-profit industry, oversell is a huge temptation and that risk needs to be made transparent to consumers.

Second, the 23andMe test is being sold directly to individuals who may not have any knowledge of genetics. The tendency to convert risks into certainty is higher than ever. The knowledge they sell is a set of probabilities, and further, those probabilities are not stable. The consumer may not—indeed probably doesn’t—appreciate how much we know, how much we don’t know, and how much we don’t even know we don’t know. The company claims to be selling knowledge but in fact they are selling uncertainty.

In a characteristically insightful and clarifying post, the geneticist (and 23andMe board member) Michael Eisen doubts whether the 23andMe test will ever meet FDA’s definition of a “medical device.” It is not an MRI machine or a Wasserman test. It’s something new. Adequate regulation of products such as the 23andMe genome profile will require rethinking of what exactly the company is marketing.

Putting this controversy in context, then, illustrates another critical risk: the risk of failing to acknowledge the uncertainty underlying the science. In some sense, the more we learn, the less we know.

[1] Orkin, S. H., and A. Motulsky. Report and Recommendations of the Panel to Assess the NIH Investment in Research on Gene Therapy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1995.

Like this:

Like Loading...

You must be logged in to post a comment.