A flurry of eugenics-related news over the last couple of weeks demonstrates that we have to stop considering eugenics a historical period and think about it more as an ever-present theme. In my book I called it “the eugenic impulse”—not to invoke some sort of misty, mystical force but rather simply to point to something that seems deeply part of our nature. Which is not to say part of our DNA. My research convinced me of two things:

1) Mixed with the chauvinism, intolerance, and paternalistic governmentality of Progressive-era eugenics was an impulse to prevent disease and disability using state-of-the-art knowledge of heredity.

2) Mixed with present-day impulses to prevent disease and disability using state-of-the-art knowledge of heredity is a great deal of hype motivated more by the desire for profits than by humanitarian concerns.

In short, I could not escape the conclusion that some aspects of contemporary genetic medicine—both good and bad—are indistinguishable from some aspects of Progressive-era eugenics—both good and bad.

The Science of Human Perfection is my attempt to wrestle with the question, “Is eugenics ever okay?” Because I have refused to come down on the side of the dogmatic anti-eugenicists, some pro-eugenics types, eager for recruits, have marshaled my words for their cause. At the same time, some antis have accused me of supporting the enemy. If I make the argument that modern medical genetics comes from the same rootstock as Progressive-era eugenics, they fear that anti-abortion fanatics will use my work as ammunition to repeal Roe v. Wade.

To those of you on both extremes, here’s my answer: No, eugenics is not okay. It scares the crap out of me, to be honest. But it’s happening anyway. No one—and certainly not a historian—is going to stop us from using genetic technology in the attempt to perfect the human race. The most intelligent response is to point out (and so hopefully avoid) the greatest risks.

*

For years, historians of eugenics have maintained that the term eugenics is no longer helpful. It is too loaded, they say; invariably, it invokes the Nazi past. Whatever programs in controlled breeding or self-directed evolution may be going on, it’s alarmist and a distraction, they say, to call them “eugenics.” For years, this was a reasonable and level-headed response, but it is no longer viable. Not because it’s less loaded, but because today’s historical actors are using it.

A growing number commentators from within the scientific community are arguing for a revisitation of eugenics:

“Seeing the bright side of being handicapped is like praising the virtues of extreme poverty. To be sure, there are many individuals who rise out of its inherently degrading states. But we perhaps most realistically should see it as the major origin of asocial behavior that has among its bad consequences the breeding of criminal violence.” (James Watson, “Genes and Politics,” 1997)

“We are once again practicing a sort of eugenics” (Matt Ridley, “The New Eugenics,” 2000)

In 2001, the conservative theorist Richard Lynn published Eugenics: A Reassessment, which argues just what you think it does. In 2002, researcher DJ Galton (no relation to the founder of eugenics) considered the new genetics, test-tube babies, and genetic screening and called a spade a spade: Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century.

“Eugenics failed because it was not scientific enough…The role of eugenics in our time is in maximizing [hereditary] information and its availability to those who need it and minimizing the temptation to use the State as the means of enforcing eugenic ideals.” (Elof Carlson, “The Eugenic World of Charles Benedict Davenport,” 2008)

“A new interest in rational discourse about eugenics…should be our goal.” (Maynard Olson, “Davenport’s Dream,” 2008)

“Soon it will be a sin of parents to have a child that carries the heavy burden of genetic disease. We are entering a world where we have to consider the quality of our children.” (Bob Edwards [creator of first test-tube baby])

“Eugenics, once discredited as part of the first wave of social authoritarian progressives that trampled free will for women, handicapped people and minorities, is attempting a 21st century comeback.” (Hank Campbell, “Genetic Literacy Project on Neo-Eugenics,” 2012)

“To a great extent we already live in the second age of eugenics.” (Razib Khan, “Eugenics, the 100 year cycle”, 2012)

The most recent is Jon Entine, who runs the Center for Genetic Literacy and writes regularly for the conservative money magazine Forbes. “Instead of being driven by a desire to ‘improve’ the species,” he writes, the “new eugenics is driven by our personal desire to be as healthy, intelligent and fit as possible—and for the opportunity of our children to be so as well.” (Jon Entine, “DNA Screening is Part of the New Eugenics—and That’s Okay,” 2013)

No, we are not trying to improve the species—just our children, and our children’s children, and our children’s children’s children,…

Talk of a new eugenics, then, is no longer idle hand-wringing. When our actors themselves are using the term, historians and philosophers need to take notice and help make sense of it.

*

The fact that Entine writes for Forbes, Ridley for the National Review, and Lynn for Mankind Quarterly suggests a linkage between the new eugenics and conservative ideologies. Eugenics has long had such associations. Some of the neo-eugenicists (e.g. Lynn) are ideologically linked to the old, discredited eugenic ideologies. But others (e.g., Ridley, Entine) I think are more complicated. Liberals and conservatives, of course, are a diverse lot. When critiquing neo-eugenics, we must bear in mind whether someone is writing from a position of profit-making, preservation of the social status quo, libertarian individualism, or other ideology.

Further, liberals can be eugenicists too. As Diane Paul showed years ago in “Eugenics and the Left,” political liberals were also deeply involved in eugenic schemes during the Progressive era. Most historians of eugenics agree that to a first approximation, everyone in the Progressive era was a conservative. Sterilization legislation was democratically approved, and most sterilizations were carried out in state hospitals, under at least a premise of social benefit. There may well have been a conservative slant to Progressive eugenics, but it was only a slant, and by the 1930s eugenics probably had a liberal slant.

Because of this political ecumenicalism, eugenics today makes for some strange political bedfellows. If some pro-eugenics advocates lean conservative, so do some antis. The Catholic Church—hardly a bastion of liberal fanaticism—opposes eugenics on grounds that it generally entails either abortion or embryo selection. Matt Ridley favors eugenics and is a pro-business conservative. Genetic screening can be seen as a liberal, feminist issue—an issue of women’s choice and empowerment. Or it can be seen as a tool of government social control. Finally, genetic screening and eugenics are not necessarily the same thing. The Center for Genetics and Society supports abortion and genetic screening but seeks to establish a critical biopolitics that can help shape policy to reap the benefits and avoid the risks of reproductive technologies—a position Entine constantly takes them to task over, presumably because they are not simple cheerleaders.

Eugenics, then, does not hew unswervingly toward either pole of the political spectrum. The eugenics question forces us to parse some traditionally liberal and conservative ideas in new ways. Favoring genetic technology is pro-business (conservative). Favoring prenatal genetic diagnosis with abortion is pro-choice (liberal). Fearing the power of genetic manipulation falling into the hands of totalitarian regimes: liberal. Favoring open markets and “consumer choice”: pro-business conservative. Sometimes this consumer-driven eugenics is even called “liberal eugenics.” Perhaps that’s a smokescreen, but maybe not entirely.

Political ideology, then, can’t help us make an easy decision on whether eugenics is ever okay. If the new eugenics has a conservative tilt it’s only a tilt, and there’s plenty of counterweight on the other side. Unfortunately, we’re going to have to make up our own minds.

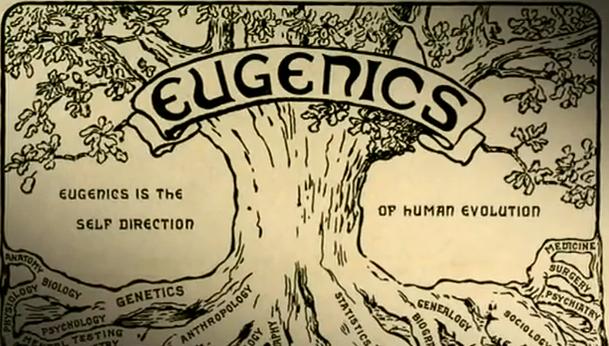

To do that, we first have to accept that the eugenic train has left the station. Understood as “the self-direction of human evolution” (the slogan from the 1921 eugenics congress and for me still the most inclusive definition I’ve found), eugenics is going to happen. Is happening. Always happens. For now, it’s still mainly for elites who can afford expensive IVF and genetic screening, but the cost of those procedures is dropping rapidly and more people are gaining access to it each year. Many people are in fact currently making eugenic choices, from the wealthy who can afford prenatal genetic diagnosis with selective abortion to the Dor Yeshorim who screen for and discourage marriage between carriers of Tay-Sachs and a range of other genetic diseases. On this much, I agree with folks like Entine. Where we part company is that I’m not nearly so sanguine about it as he seems to be.

Recognizing that we are grasping the reins of human evolution as fast as we can raises two sets of concerns. First, “What if it doesn’t work?” It’s been argued for some time that our technological capacity greatly outstrips both our wisdom and our understanding. It’s often argued that genetic choices have been made since the dawn of marriage, so opposition to techniques such as embryo selection is mere technophobia. But even age-old holistic breeding practices have unpredictable, undesired effects. Sweet-tempered Laborador retrievers tend to get hip dysplasia and eye problems. Great Danes’ hearts fail. Some quarter horses are prone to connective tissue disorders or “tying up” episodes related to their highly bred musculature. The European royal families are prone to hemophilia and polydactyly. Selecting for single genes, rather than traits that involve suites of genes that have evolved together, seems likely to exacerbate such unintended consequences. The emerging science of systems biology holds that genes act—and hence evolve—in networks. Selecting for particular genes rather than complex traits disrupts those networks and is likely to have unpredictable effects.

We in fact have very little idea how the genome works. The genome is like an ecosystem, a brain, or the immune system: an immensely complex, deeply interconnected system. Altering one element or a few elements has effects that are not only unknown but in many cases unpredictable. Evolution, Darwin showed, is an immensely slow process, in which innumerable parts “negotiate” with one another to produce the best-adapted organisms in a given environment at a given time. In taking control over that process, we will be altering the “ecology” of the genome, and it’s bound to have similar effects to our impact on the environment. With great wisdom, it might be handled safely, but experience does not give one much hope for collective human wisdom.

The second concern is, “What if it does work?” What if it does indeed become possible to select traits—health, height, complexion, intelligence—without creating cruel monsters? I have enough faith in technology that I think this may eventually happen. Some unforeseen consequences will doubtless occur, but in time they will become correctable. So what do we do when this becomes possible? We need to keep in mind that this will be a tool of the upper strata of society for a good long time. The rich will do it more than the poor, and Americans and Europeans will do it more than Bangladeshis and Somalians. So it will be a way of inscribing socioeconomic status literally in our DNA. This is in fact a conservative application, because it will tend to reinforce the socioeconomic status quo.

Further, in most developed countries, it’s not government control we need to worry about; it’s corporate control and the tyranny of the marketplace. Advertisers will push certain genotypes. Ad campaigns, current styles, and the rapidly shifting current consensus on what is or is not healthy will shape people’s genetic decisions. And of course, you can’t shed your genome the way you can last year’s fashions. The concern here, then, is that the new eugenics harnesses long-term processes in the service of short-term goals. This too will have unpredictable effects. History shows without a doubt that societies are rarely wise; we have great trouble seeing several moves ahead, planning for the future, delaying gratification, or sacrificing some of next quarter’s earnings so that we may reap greater health and happiness some time in the future. Even more troubling than failures of technology, then, are failures of morality. And glib reassurances that we are beyond Nazi-style totalitarianism do little to comfort me. The age of self-interested individualism can be just as scary as that of communal self-sacrifice.

Most critical analyses of past eugenic efforts have centered on race, class, and gender. I think that the greatest concern with the new eugenics will likely be the fourth member of the “big three”: disability. Another recent story concerns the stunning development of a method of “silencing” chromosomes. Every nucleated cell in a woman’s body uses this to turn off one of her two X chromosomes; otherwise, women would have a double dose of X chromosome genes, which would lead to lots of problems. The advance is in harnessing this technique so that it can be applied to non-sex chromosomes. Down syndrome results from an extra (third) chromosome 21. The blogs and papers have been awash lately with speculations about “shutting off” the extra chromosome 21 in embryos, to prevent Down syndrome.

The problem is that the severity of Down’s is unpredictable. A family might well be happy to have a high-functioning Down’s baby, but a severely affected child suffers greatly, as does its parents. Who would take that chance? If (when) this technique becomes widely medically available, the frequency of Down syndrome will drop, simultaneously reducing suffering among the victims and families of severe Down’s and joy and love among those close to high-functioning Down’s patients. No humane person would never wish, say, Down syndrome on a family not equipped to handle such a child. But nor would I want to live in a society lacking in people with Down syndrome, or little people, or the blind. It’s not a wish for suffering; we all suffer. But engineering our own evolution will likely have a normalizing effect. Intolerance of abnormality was, indeed, a common refrain among Progressive-era eugenicists and greater power over our genetic future is only likely to increase it. The movie GATTACA got this much right: genetic disease leads to suffering—but so does intolerance.

Is eugenics ever okay? On the individual scale, of choosing not to raise a child with a debilitating disease, I think we have no moral choice but to condone it. A prospective parent talking with a genetic counselor about whether to prevent a deformed or diseased baby from being born is in fact a form of eugenics. But my research made it irrefutable that eugenics has always been simultaneously about individuals and populations. Individual choices lead to population changes—and individual choices are influenced by more than objective genetic knowledge. Although those parents’ choice is for their family rather than the race, they are simultaneously participating in the self-direction of human evolution—it is a choice that any Progressive-era eugenicist would have condoned. And, granting the right to abortion and embryo selection, that is an entirely moral choice.

But what influences that parent’s choice? The biomedical industry hides truly fantastic profits behind the cloak of “health.” Moving responsibly into this inevitable future demands that someone call out the self-interest of the diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies, the instrument-makers and laboratories, the hospitals, the advertisers, and the investors in this new age gold mine. It demands analysis of subtle forms of coercion. It demands a jaundiced eye. Skepticism isn’t Luddism, isn’t anti-choice, isn’t anti-health. It’s following the money.

Much as one might wish to do so, the genie can’t be stuffed back into the bottle. The new eugenics is here. This worries me greatly. But worry, by itself, solves nothing. The concerns it raises are too complex for either dogmatism or complacency. It comes with new, subtle kinds of coercion. Science alone cannot be our guide into this brave genetic world. The closer we come to guiding our own evolution, the more important a humanistic perspective—one that takes the long view of history and the broad view of social context—becomes in helping us make sense of it. The future is here, and, dammit, it’s complicated.

[Update 7/26/13 3:20 pm: Changed description of the Center for Genetics and Society to more accurately reflect their philosophy and agenda. H/t Alex Stern.]