(Reprinted, with minor revisions, from “Is individuality the savior of eugenics?” at Scientific American blogs)

Is eugenics a historical evil poised for a comeback? Or is it a noble but oft-abused concept, finally being done correctly?

Once defined as “the science of human improvement through better breeding,” eugenics has roared back into the headlines in recent weeks as both Mr. Hyde and Dr. Jekyll. The close observer may well wonder which persona will prevail. The snarling Mr. Hyde is the state control over reproduction. Although this idea may evoke visions of Nazi genocide, the U.S. itself has a long, unsavory eugenic history, stretching through much of the 20th century. And now it extends into the 21st: the recent investigation by the Center for Investigative Reporting, which showed that between 2006 and 2010 nearly 150 pregnant prisoners had been sterilized against their will in California, was a stunning reminder that traces of the old eugenics remain in our current century. Another recent story—a polemical but informative three-part series on the continued efforts of Project Prevention, a private effort begun in 1997 that pays poor and drug-addicted women to be sterilized—highlights some of the complexities of reproductive rights. Payment of the poor or incarcerated has long been acknowledged as a form of coercion; yet some such women genuinely welcome the opportunity not to bear more children they cannot afford without curtailing their sex lives. Sorting out these issues has been a problem at least since North Carolina’s eugenics program, begun in the 1940s, which sterilized thousands through the 1950s and 1960s, with the express approval of the state. A dabbing of eyes and collective sigh of closure accompanied the news this month that the North Carolina legislature will pay a total of $10 million to the program’s victims, or, as they were known at the time, patients.

Eugenics critics are still the vocal majority, spanning the political spectrum. But in recent years, a growing constituency of Drs. Jekyll within the biomedical community has sought to resurrect eugenics as something that, if done correctly, can bring about marvelous benefits for humankind. The key to the new eugenics, they say, is individuality—a word with complex resonances ranging from “individualized medicine” to individualism, a cherished American value. Indeed, the new eugenics is sometimes called “individual” eugenics. A recent article by Jon Entine, of the Center for Genetic Literacy at George Mason University, exemplified this push for eugenicists to come back out of the night. Prenatal genetic diagnosis is eugenics, Entine says—“and that’s okay,” because it is controlled by individuals, not governments. This sparked a lively debate on both his blog and mine. To those following the discussion this summer, individuality seems to be fighting for the soul of eugenics.

*

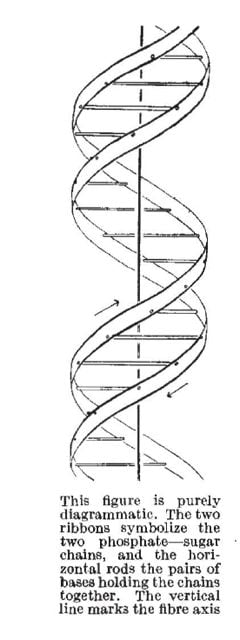

Individuality is one of the oldest and newest terms in medicine. The Hippocratic physicians acknowledged that each patient was a unique, individual constellation of heredity, environment, and experience (although individualized treatment was, as today, reserved for those who could afford it). In the second century A.D., Rufus of Ephesus stressed the importance of interrogating the patient as to habits, preferences, experiences, and congenital diseases as an aid to diagnosis. The development of the case-study method in the Early Modern period signaled new attention being focused on the individual; each case came to be understood as a unique manifestation of disease. Yet one of the greatest transformations in medicine—the 19th century concept of specific disease, caused by a specific disease agent such as the cholera vibrio or the tubercle bacillus—shifted the physician’s gaze from the patient to the disease. Although this development led to enormous gains in the potency of medical therapy, some have rued the disappearance of the “sick man.” The current fad for “individualized” or “personalized” medicine is, among other things, the latest call for a return to patient-centered medicine. Increasingly, the physician interrogates the patient’s genome, learning far more from the sub-microscopic ticker-tape of DNA in her cells than Rufus’s wildest dreams could conjure.

But some question whether this new technology really puts the person back into medicine. Critics point out that personalized medicine often seems to concern profit more than health. Indeed, tech business sites show that personalized medicine is one of the healthcare industry’s biggest growth areas. Cui bono? Here is where individuality meets individualism—the libertarian swing that has captured much of American culture in recent decades. Events as disparate as the stock-market bubble, gay marriage, legalization of marijuana, and “right-to-carry” laws illustrate the resurgence of this quintessential American value. Individualism, of course, runs deep in the American identity, but not since the Gilded Age have the individualist mythos and free-market economics enjoyed such dominance. Indeed, the main arguments in domestic politics today seem to concern how and how fast to cut costs and disempower the government. Individualized medicine can be seen as individualist as well: many advocates stress that the new medicine must be “participatory,” meaning that the patient has increased responsibility for their own care. Modern individualism means everyone looks out for their own interests—from biotech CEOs to hospitals to patients.

*

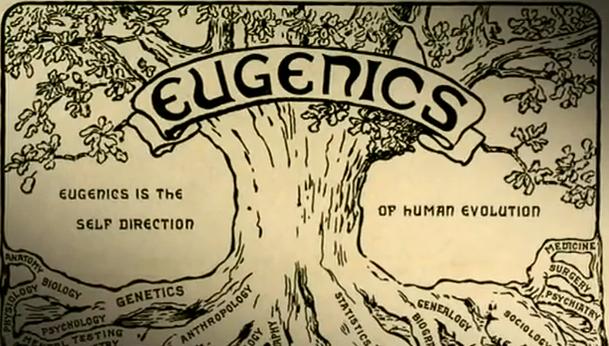

The old eugenics was top-down and collectivist. Francis Galton proposed eugenics in Victorian England, as a humane alternative to the ruggedly individualist but misleadingly named social Darwinism. (More accurate though less sonorous would have been “social Spencerism,” after Herbert Spencer.) Rather than letting the weak kill off themselves and each other, Galton proposed a system of tax incentives and education programs he thought would lead the poor, sick, and stupid to voluntarily have fewer children—and the healthy, wealthy, and wise to voluntarily breed like rabbits. Human evolution could thus be gently directed toward perfection with much less suffering. Galton counted on evolution’s losers to unselect themselves, for the greater good.

After 1900, eugenics became yet more collectivist and much more potent, particularly in Progressive-era America. Progressivism was, fundamentally, a reaction to the exploitative practices of what Mark Twain called the “Gilded Age”—the industrial boom of the 19th century. Americans were fed up with the selfish greed and worker exploitation of Andrew Carnegie (an avid social Spencerist), Cornelius Vanderbilt, JP Morgan, and the other “Robber Barons.” (The fact that the history of American industrialism is more complicated than this doesn’t alter the mythos that motivated people at the time.) Progressives counted on Government as the only social entity powerful enough to stand up to industry, but even many who did not identify with the Progressive Party valued personal sacrifice for the greater good. The first part of the twentieth century was, by American standards, a moment of profound shift toward collectivism. However, progressivism was also about science. The rediscovery of Mendel’s principles in 1900 seemed to do for heredity what Marie Curie’s radium and Rutherford’s splitting of the atom did for physics: crack open the secrets of nature, providing hitherto unknown power to harness natural forces for the good of humanity.

The combination of collectivism and science could be deadly. Progressive-era eugenics grew highly coercive and—as politics always does—reflected the prejudices of the day. State after state passed laws that prevented miscegenation, restricted marriage, and permitted sterilization without consent for people with “defects” ranging from epilepsy to mild mental retardation to tuberculosis. Congress heard testimony from arch-eugenicist Harry Laughlin before passing the restrictive 1924 Johnson Immigration Act, and, to his great pride, Laughlin’s “Model Sterilization Law” served as the basis of the Nazi eugenic law of 1933. Thirty-five states ultimately had sterilization laws on the books. Contrary to widespread belief, the Second World War did not crush the eugenic spirit, though it did modulate it. Eugenics became increasingly medicalized. For example, the North Carolina eugenics program was run by credentialed, even distinguished physicians and scientists. Although coerced sterilizations dropped sharply during the Cold War, many of the laws remained on the books into the 1970s.

Not entirely coincidentally, about that time, “eugenics” became a dirty word. Even through the 1960s, it was possible for respected scientists to write that eugenics had a “sound core,” despite having been abused by the Germans. The conscious betterment of our gene pool, the self-direction of human evolution, had been a goal of human genetics throughout the field’s history. But by the 1980s, explicit discussion of eugenics had become Verboten, and even eugenics critics tended to think that the term had simply become too loaded to be productive. Calling someone a eugenicist was tantamount to calling him a Nazi.

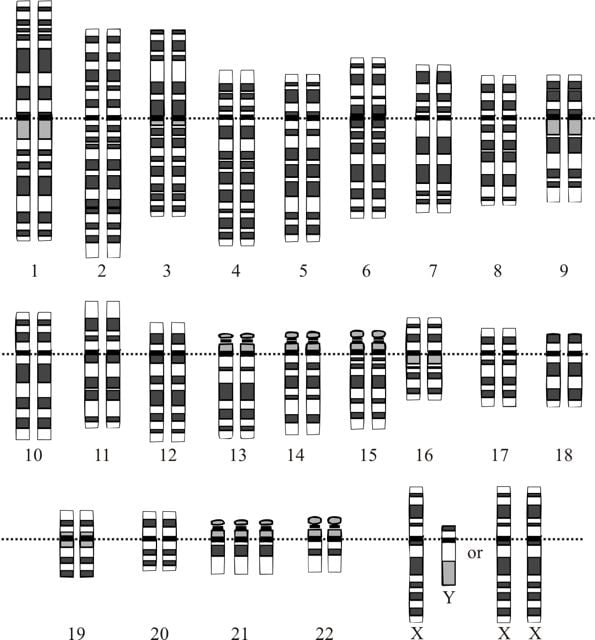

It is fascinating, then, to watch a small but growing contingent within the scientific community begin to use “eugenics” again voluntarily, even proudly. In recent years, authors such as DJ Galton, Nicholas Agar, John Harris, Matt Ridley, Julian Savulescu, and others have argued that it is time to reopen a discussion of eugenics. Like the original Galtonian eugenics, this new eugenics was voluntary and aspirational, but it traded collectivist altruism for personal choice. Some of the new eugenicists were coy about the term: “In point of fact, we practise eugenics when we screen for Down’s syndrome, and other chromosomal or genetic abnormalities,” said Savulescu in a 2005 interview. “The reason we don’t define that sort of thing as ‘eugenics’, as the Nazis did, is because it’s based on choice. It’s about enhancing people’s freedom rather than reducing it.” However, others called a spade a spade. Agar, for example, used a similar argument about choice—“prospective parents should empowered to use available technologies to choose some of their children’s characteristics”—but titled his 1998 book Liberal Eugenics.[1]

*

Modern medicine, yielding to the demands of real progress, is becoming less a curative and more a preventive science. From an art of curing illness, it is becoming a science of health. It is safe to predict, I believe, that…medical men generally will be more of the order of guardians of the public health than doctors of private diseases.[2]

Though they could stand as an epigram for genomic individualized medicine, those words were written one hundred and one years ago, in an article called “Eugenics and the medical curriculum,” by Harvey Ernest Jordan, later the Dean of Medicine at the University of Virginia. His next sentence, however, gives away that he is writing in 1910, not 2010: “This represents the medical aspect of the general change from individualism to collectivism.” To adapt Jordan’s quote to our century, we’d only need to reverse those last three words. Collectivism is now anathema.

Today’s nouveau eugenicists argue explicitly that the general change back to individualism is what defangs the new eugenics. In Cold Spring Harbor’s 2008 reissue of Charles Davenport’s big book, 1910’s Heredity and Eugenics, Matt Ridley writes,

There is every difference in the world between the goal of individual eugenics and Davenport’s goal. One aims for individual happiness with no thought to the future of the human race; the other aims to improve the race at the expense of individual happiness.[3]

First, that remark is disingenuous. “Control and nothing else is the aim of biology,” wrote Jacques Loeb in 1905.[4] Efforts such as the J. Craig Venter Institute’s efforts to engineer life “from scratch” or the “BioBricks” project—an open-source genetic engineering project, like SourceForge for wetware—make clear that designing living things from the DNA up is a conscious and widespread goal. It cannot but merge with medicine eventually. Further, concern for individual happiness has never been mutually exclusive of concern for the race. In 1912, Charles Davenport recognized this in 1912 when he wrote that physicians have an obligation to practice eugenics, for the individual, for the family, for the community, and for the race. Concern for your individual child is concern for a member of your family lineage. Savulescu’s principle of procreative beneficence—that one has a moral obligation to bring the best children possible into the world—grades into the view that we have such an obligation, collectively. Individual eugenics, in other words, becomes a species of collective eugenics.

Second, is giving no thought to our future truly anodyne against disaster? If collectivism carries the risks of the slavish embrace of ideology and the concentration of power, individualism carries the risks of selfishness and lack of foresight. Consider other individualistic approaches to technology—to name but one example, the impact of technology on our climate. Aiming for individual happiness with no thought to the future of the human race has led to countless inventions that provide individual happiness for millions of people every day: air conditioning, automobiles, smartphones, cheap food, global travel, and much more. However, all these devices and industries contribute massively to climate change. We have understood the climatic effects of anthropogenic CO2 for decades, but individual happiness (including not least that of the corporate CEOs) has trumped any thought for the future. We have, in short, altered an enormously complex system without meaning to, and the results, according to scientific consensus, may be catastrophic.

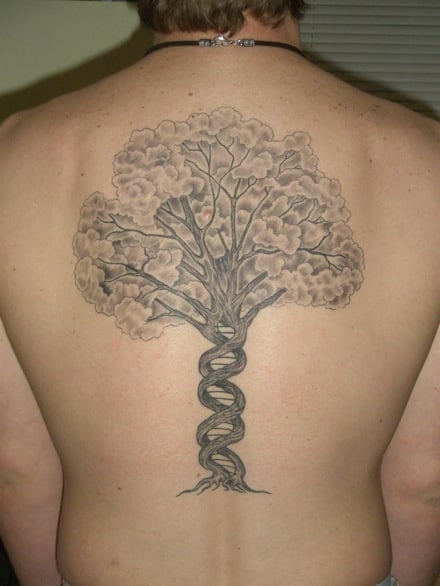

Our genome creates a climate within our body. Recent findings make clear that it is a dynamic, complex system—a “sensitive organ of the cell,” as Barbara McClintock wrote presciently in 1984. Under this view, Progressive-era marriage and sterilization laws regulated whole bodies and their relations, while modern genomics regulates single genes and their relations. Bringing the decision within the body’s boundaries makes individual choice possible. But it also disrupts a complex genetic ecosystem, which any scientist will admit we know almost nothing about. Our knowledge of this ecosystem is changing incredibly rapidly; it is certain that in 20 years, today’s knowledge will seem almost incomprehensibly primitive. Almost inevitably, then, altering individual components of the system in isolation will have unforeseeable consequences. Dog breeders, exercising individual choice, produced modern Labrador Retrievers, a breed blessed with qualities of temperament, strength, and beauty, but plagued by eye problems and a tendency to hip dysplasia. Selection at the level of individual genes is likely to increase, not decrease, such problems. Individual choice, then, is subject to pressures of fashion and the profit motive, which are no better guides to evolution than bureaucracy.

In short, as blogger Razib Khan has noted, we already live in the new age of eugenics. But we shouldn’t delude ourselves that the latest political pendulum swing immunizes us against its risks. Individualism solves the problems of collectivism in mirror image of the ways that collectivism solves those of individualism. To treat either approach as a panacea is both naive and dangerous. The sociologist Nikolas Rose argues that our health status is becoming more important than our labor in shaping our identity. Many people today may find more in common with a fellow cancer victim or celiac sufferer than with a fellow plumber or banker. Such “biological citizenship” will obviously be profoundly influenced by genome screening, prenatal diagnostics, and other techniques of the new eugenics. This fact should remind us that although our identity may be unique, it is never isolated. We are all individuals within a collective.

References

Comfort, Nathaniel. The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine. Yale University Press, 2012.

———. The Tangled Field: Barbara Mcclintock’s Search for the Patterns of Genetic Control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Davenport, Charles. “Eugenics and the Physician.” New York Medical Journal June 8 (1912): 1195-99.

Jewson, N. C. “The Disappearance of the Sick-Man from Medical Cosmology, 1770-1870.” Sociology 10 (1976).

Schoen, Johanna. Choice & Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Stern, Alexandra Minna. Telling Genes: The Story of Genetic Counseling in Modern America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Rose, Nikolas. The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Rufus of Ephesus. “On the Interrogation of the Patient.” In Greek Medicine, Being Extracts Illustrative of Medical Writers from Hippocrates to Galen, edited by Arthur John Brock. xii, 256 p. New York,: AMS Press, 1972.

Nathaniel Comfort is Associate Professor of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. He is the author, most recently, of The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine (Yale, 2012). He also writes the blog Genotopia (http://genotopia.scienceblog.com) and can be followed on Twitter at @nccomfort.

[1] Agar, Nicholas. “Liberal Eugenics.” Public Affairs Quarterly 12, no. 2 (1998): 137-55, p. 2.

[2] Jordan, H. E. “The Place of Eugenics in the Medical Curriculum.” In Problems in Eugenics: Papers Communicated to the First International Eugenics Congress. 396-99. Adelphi, W. C.: Eugenics Education Society, 1912.

[3] Ridley, Matt. “Davenport’s Dream.” In Davenport’s Dream: 21st Century Reflections on Heredity and Eugenics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2008, ix-xi.

[4] Loeb, Jacques. Studies in General Physiology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1905, ix.

You must be logged in to post a comment.